Focus - July 2020

Special considerations for the older patient

Maria Mulvihill DVM focuses on the work up and preventative care for a number of conditions that occur frequently in older animals

The age category that constitutes a geriatric dog or cat is not easily defined in veterinary medicine. In human medicine, people are considered elderly or geriatric from the age of 65, however we do not have specific requirements in dogs and cats.1 There are several studies in the literature that have suggested specific ages at which dogs and cats should be considered ‘old’ depending on breed and size.2 That being said, an advanced age does not predict mortality as ageing composites different biological processes characterised by ongoing modification of tissues and cells with a gradual loss of adaptive capacity.3 Signs of ageing are inevitable in older dogs and cats and veterinarians mostly rely on observations by the pet owners to characterise disease course and duration. Common presenting complaints include external changes visible to the owner such as slowing down/mobility issues, loss of vision, loss of hearing, haircoat (alopecia, colour changes), behavioural changes, changes in eating or drinking habits and weight loss/gain.4 This reliance on owners to assess disease in their pets can lead to delayed recognition and intervention as they fail to report cardinal signs of disease or recognise the importance of signs in their dog or cat. Therefore, routine screening with physical exam findings, bloodwork, and imaging (thoracic radiographs or ultrasound), are paramount in the continued management and improved quality of life of geriatric patients.

Complete discussion of disorders that affect geriatric dogs and cats is beyond the scope of this article, so the author will focus on the work up and preventative care for a few conditions that occur frequently in older animals.

Physical exam findings

As discussed, evaluation by a veterinary practitioner can reveal abnormalities that have not been considered by an owner. Outlined below are some considerations to keep in mind in ageing pets. This is not an extensive list and should not replace a thorough history or physical examination including a rectal examination.

- Weight

Basic information such as trending weight and changing body condition score should be included in each visit. Significant changes in weight should be investigated as it may indicate underlying pathology. A dog with painful orthopaedic disease will be less mobile and can be predisposed to weight gain that may go unnoticed by the owner.5 Early metabolic or endocrine disease such as chronic kidney disease or hyperadrenocorticism can cause subtle changes in muscle mass in early disease.6

- Heart murmur

A newly recognised heart murmur in an older dog or cat should be worked up to determine an underlying cause. Veterinarians are cautioned against initiating therapy (eg. inodilators such as pimobendan) without cardiac imaging of any kind, with a definitive diagnosis guiding treatment protocols. Extracardiac causes of a murmur, such as pulmonary hypertension should be considered in a geriatric patient. Pulmonary hypertension exhibits similar clinical signs to heart disease (exercise intolerance, cough, dyspnoea and syncope), can occur concurrently with mitral disease and warrants a different prognosis.7 Research does not support the treatment of asymptomatic dogs with mitral valve-associated systolic heart murmurs alone (regardless of intensity) or dogs that do not exhibit evidence of cardiac enlargement on radiographs or echocardiogram.8

The author recommends evaluation by a board-certified cardiologist; however, financial or geographical limitations may inhibit this option. Thoracic radiographs can screen for cardiac and atrial enlargement; however, for any suspicion of cardiac abnormality (radiographic, clinical or historical) echocardiography is indicated as inappropriate patient positioning and exposure can lead to inappropriate diagnosis of heart disease. The previously described vertebral heart score (VHS) has been used as a quantitative measurement of heart enlargement.9 Due to the wide variations in measurements in normal dogs and cats and reader interpretations, the best use of the VHS is to compare cardiac size on serial radiographs of the same patient made over time to monitor disease progression or response to treatment.10

There are some age-, breed- and body habitus-related changes that should be taken into consideration when evaluating the heart. With regard to body habitus, muscular dogs or those with a barrel-shaped thorax (such as brachycephalic breeds, beagles and basset hounds) have a cardiac silhouette that looks large. Alternatively, the normal cardiac silhouette in deep-chested breeds such as greyhounds, can look abnormally small.10

Cats have much less patient-to-patient variation in the radiographic appearance of the heart, and there is much less of an effect of radiographic positioning. Age-related cardiac silhouette changes in the cat include increased sternal contact and fat in the mediastinum adjacent to the heart that can cause a false impression of cardiac enlargement.10

With some training, non-cardiologist/non-radiologist veterinarians can achieve proficiency in identifying left atrial enlargement. The left atrium is most commonly compared to the aorta in a right-sided, short-axis view at the base of the heart or a long-axis view. A normal left atrium/aorta ratio (La:Ao) is less than 1.5 in cats and less than 1.3 in dogs.11 Dogs with mitral valve disease and an La:Ao ratio greater than 1.6 can benefit from treatment.8 A similar finding has not been evaluated in cats.

• Gait abnormalities: Orthopedic vs neurologic vs systemic?

Changes in ambulation and activity are easily observed in dogs and cats by owners. Owners associate decreased mobility as part of the normal ageing process and may not seek treatment. However, it may signify an underlying disease process in an older dog or cat and should be worked up by veterinarians. Clinical signs such as weakness, limping, difficulty rising, shaking/trembling and falling over should be distinguished from underlying orthopaedic, neurologic or systemic disease. Systemic diseases are often identified with bloodwork (chemistry, complete blood count, electrolyte analysis, T4, PTH, PTHrP). Targeted questioning of the owner will help narrow the differential diagnosis list (see Table 1).12 Examples include:

- How long has the problem been going on for?

- Has the problem progressed?

- Is the lameness or weakness worse or improved with exercise/rest?

- What limbs are affected?

- Does the animal seem painful?

- Has medication helped?

After a thorough history, a definitive orthopaedic and neurologic exam must then be performed to localise the affected area. One must take into account normal age-related changes during the neurologic evaluation. Changes such as shortening of stride, decreases in muscle tone, slowing of pupillary reflexes and some loss of ocular motility can be seen with older animals but typically do not result in an associated change in reflex function or postural reactions.13 Neurological deficits related to cervical spinal cord compression may be seen as paresis or lameness (weight bearing or non-weight bearing) in a thoracic limb. This phenomenon, termed ‘nerve root signature’, is typically seen in small-breed dogs and presents as pain on palpation or traction of the limb. Affected animals may also frequently hold up the limb.14 Breeds at risk of neoplasia such as Labrador retriever, Golden retriever, Bernese mountain dogs, German shepherd dogs, rottweilers and greyhounds with lameness should always include radiographic imaging (thoracic radiographs and appendicular skeleton) and abdominal ultrasound as part of their work up.10

Table 1: Examples of differential diagnosis’s that cause gait abnormalities or weakness.12

Behavioural changes

Normal behaviour is predominantly controlled by the prosencephalon but requires complex coordination and integration of the entire nervous system.14 Changes in the animal's normal habits, personality, attitude and reaction to its surroundings should be investigated for an inciting cause, especially in the case of new onset seizures. Subtle changes may go unnoticed for prolonged periods of time until they become more severe. Recognition of clinical signs depend on the human-animal bond, owner perception of ageing and whether a pet is left unattended outside for prolonged periods versus an animal that is indoor only or in urban areas where owners have to walk with their pets several times a day. Clinical signs vary and include lethargy, compulsive circling, sleep disturbances and night-time waking (barking), staring at walls, getting stuck in circles, loss of learned behaviours, aggression and failure to recognise owners or familiar environments.14 Dementia should not be considered a normal ageing change, but rather a pathologic condition for which a cause should be identified. Only when the animal has a normal neurologic examination, normal ancillary blood, urine, CSF and advanced imaging studies (CT/MRI) is a psychological disturbance such as canine cognitive dysfunction considered. Along with a structural abnormality (neoplasia), encephalitis, intoxications, malformations, trauma, vascular events (ischemia, infarction) and metabolic disorders must be considered. Treatment is dependent on the underlying cause and can include surgery for accessible prosencephalic lesions, anticonvulsants, anxiolytics, environmental modification, and diet (containing antioxidants, mitochondrial cofactors, phosphatidylserine, and omega-3 fatty acids).

Euthanasia

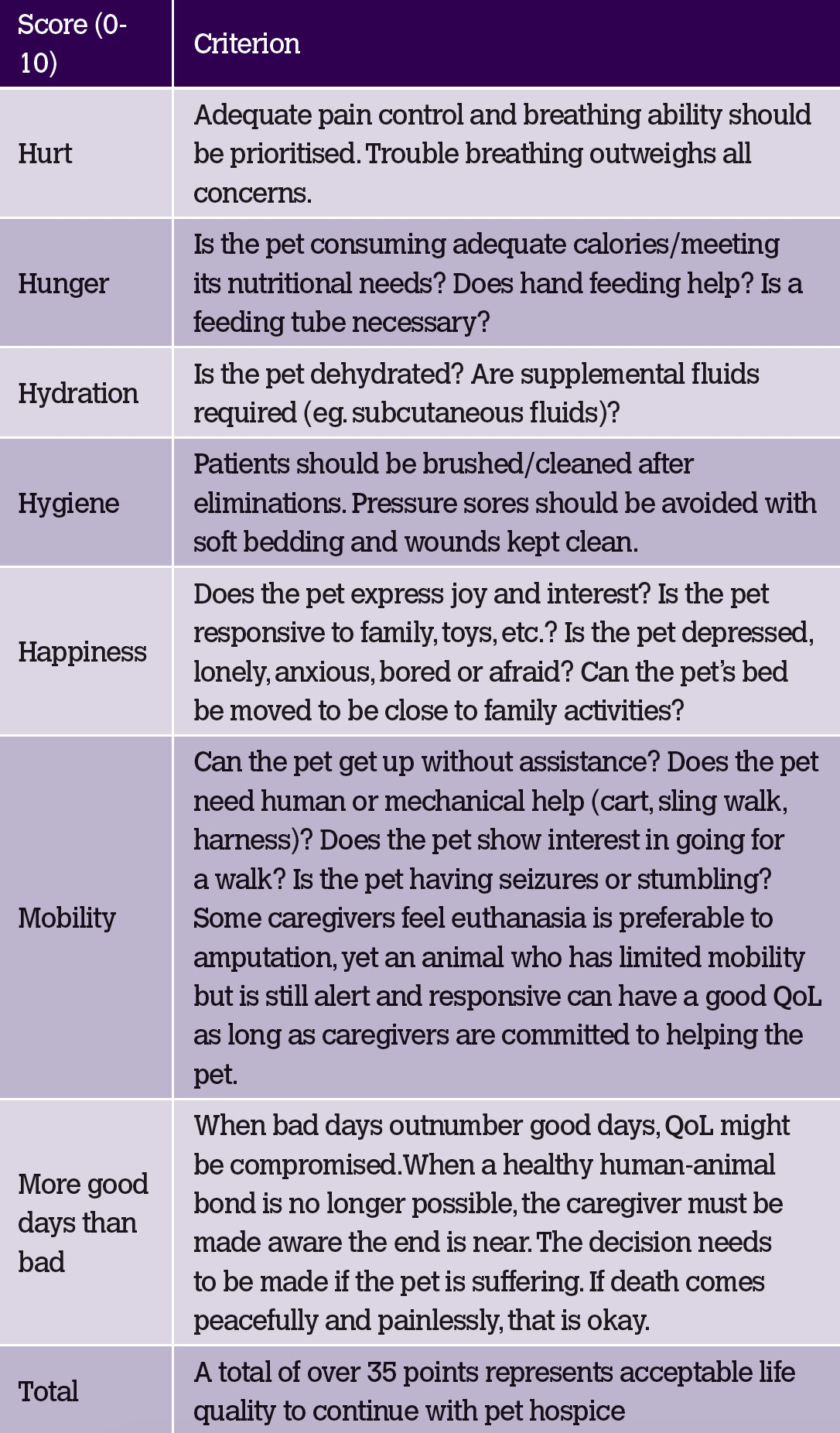

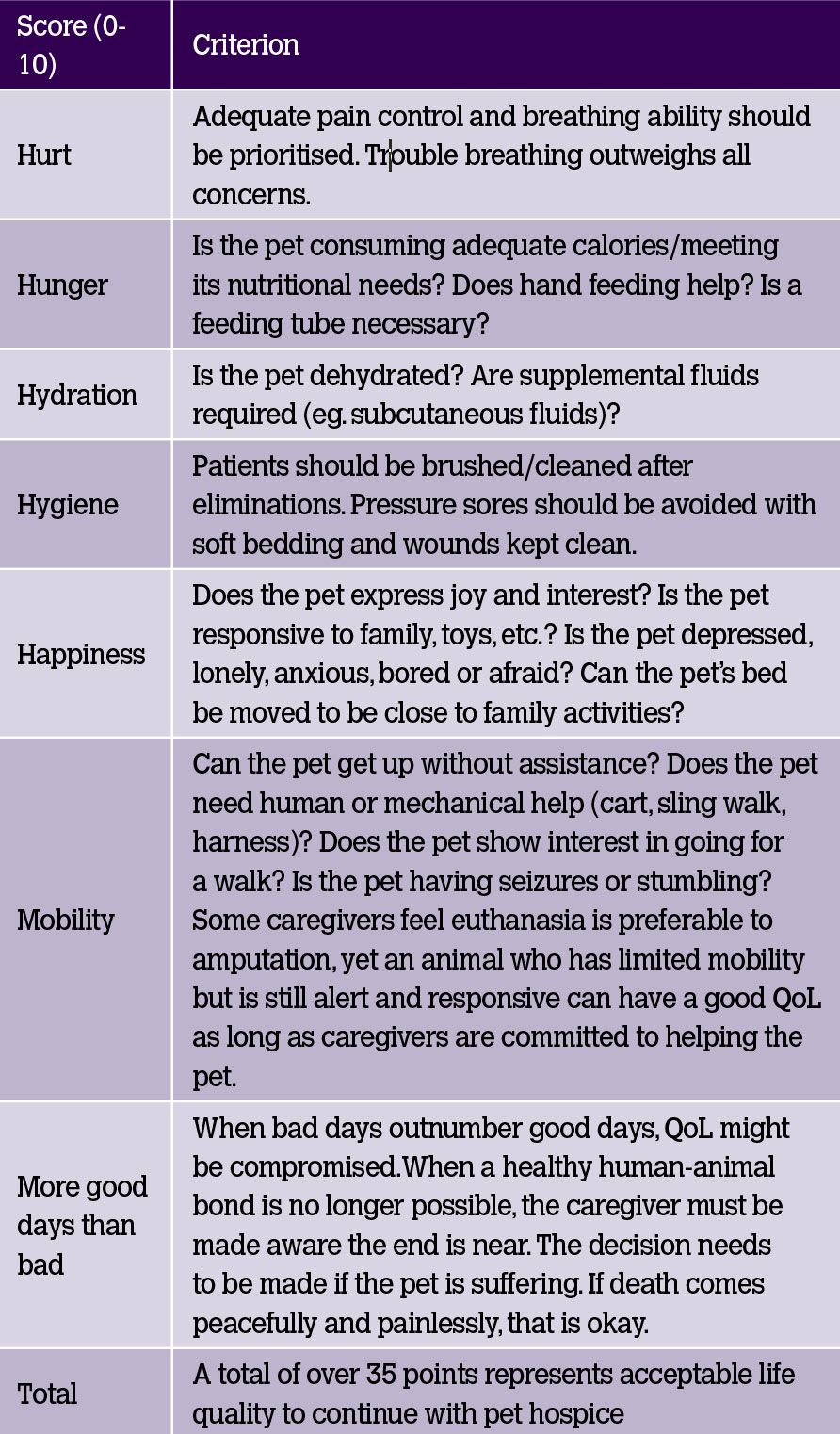

Euthanasia must be discussed in the context of geriatric medicine. The veterinary oath commits the profession to the prevention and relief of animal suffering. There is a professional obligation to properly assess quality of life (QoL) and confront the issues that ruin it, such as undiagnosed suffering. Veterinary practitioners are frequently asked to assess and weigh in on whether an animal is in pain or suffering. In cases where an illness poses a constant threat to the animal's life (eg. respiratory illness requiring supplemental oxygen) or ongoing suffering that violates the five freedoms (eg. urinary obstruction), a decision can be made readily.15 However, the author uses guidelines such as the QoL Scale (see Table 2) to help advise owners in making a decision for their pet when immediate welfare is not a concern.3 The HHHHHMM Scale is a tool that owners can easily use when considering euthanasia and may help owners in denial to confront issues that are difficult to face.

Table 2: Adapted from Canine and feline geriatric oncology: honoring the human-animal bond.3

Summary

Client education and counselling are integral parts of veterinary medicine. Its importance increases when dealing with geriatric patients. Veterinarians must provide realistic and accurate expectations for owners, with definitive diagnoses and frequent re-evaluation being the cornerstone of management in ageing dogs and cats.16

Author

Maria Mulvihill DVM is currently a small-animal rotating intern at Pieper Memorial Veterinary Center, Middletown, Connecticut, US. In addition to Pieper, she has worked in both Ireland and Dubai.

-

Sieber C. The elderly patient - who is that? Internist 2007; 48: 1190-1194.

-

Saker KE. Nutritional influences on the immune system in aging felines. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practising Veterinarian; 2004; 26:11-14.

-

Villalobos A, Kaplan L. Canine and feline geriatric oncology: honoring the human-animal bond. Blackwell Publishing (Wiley-Blackwell), Hoboken (NY); 2007.

-

Soumyaranjan P et al. Evaluation of geriatric changes in dogs. Veterinary World 2015; 8 (3): 273-278.

-

Epstein M et al. AAHA/AAFP Pain Management Guidelines for dogs and cats. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 2015.

-

Sparkes A et al. ISFM Consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of feline chronic kidney disease. Journal of feline medicine and surgery 2016; 18: 219-239.

-

Kellihan H, Stepien R. Pulmonary Hypertension in Canine Degenerative Mitral Valve Disease. Journal of Veterinary Cardiology 2012; 14 (1): 149-164.

-

Boswood A, Haggstrom J, Gordon SG, et al. Effect of pimobendan in dogs with preclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease and cardiomegaly: the EPIC study – a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2016; 30:1765-1779.

-

Deepti B et al. Vertebral scale system to measure heart size in thoracic radiographs of Indian Spitz, Labrador retriever and Mongrel dogs. Veterinary World 2016; 9 (4): 371-376.

-

Thrall Donald E. Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology. 7th Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2018

-

DeFrancesco T. Management of cardiac emergencies in small animals. Veterinary clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 2013; 43: 817-842.

-

Thompson M. Small Animal Medical Differential Diagnosis. 3rd Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2018.

-

Fenner W. Neurology of the Geriatric patient. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice; 18 (3): 711-723.

-

De Lahunta, Glass, Kent. Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology. 4th Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2015.

-

Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC). Second Report on Priorities for Research and Development in Farm Animal Welfare; DEFRA: London, UK, 1993.

-

Davies M. Geriatric screening in first opinion practice – results from 45 dogs. Journal of Small Animal Practice 2012; 53 (9):507-13.