Acute hyperkalaemia in greyhounds under general anaesthesia

Laura McKay RVN N.Cert A&CC/ECC MSc. Veterinary Anaesthesia & Analgesia, AllPets Veterinary Hospital, Co. Louth, provides an overview of recent research into acute hyperkalaemia in greyhounds under general anaesthesia

Anaesthesia-induced hyperkalaemia is a relatively recent phenomenon documented in healthy greyhounds1-5. Hyperkalaemia in dogs is defined as a potassium level greater than 5.5mmol/L6, with normal serum potassium levels in greyhounds being lower compared to other breeds (3.5-4.4mmol/l)7. Progressive increases in serum potassium negatively affect the electrical conduction of the myocardium and the potential to cause life-threatening arrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation and death if left untreated. In addition to the published literature discussed below, our clinical staff have also observed this phenomenon in greyhounds under anaesthesia in our hospital setting, which required intervention.

Background

Greyhounds have been heavily featured in the sporting arena, making them the most numerous sighthounds in Ireland. Historically, greyhound racing and coursing have been popular in Ireland. In recent decades, there has been growing concern about greyhound welfare and the excess of unwanted dogs as a by-product of the industry. Animal charity initiatives and public awareness campaigns have contributed to the growing popularity of rehoming greyhounds as family pets.

From 2008 to mid-2025, 17,809 Irish greyhounds were rehomed (figures provided by the Irish Racing Greyhound Trust [IRGT] upon request). The number of greyhounds being rehomed has been trending upwards, doubling in the latter half of this eighteen-year period. The presentation of greyhounds has become more common across all types of veterinary practices in Ireland. These dogs are now more frequently subjected to complex, lengthy general anaesthetics in both general and referral practices for treatment of conditions often associated with ageing dogs, such as dental treatment, advanced diagnostics, or, for example, limb amputation due to osteosarcoma, a common condition in the breed.

There is currently a changing demographic of greyhound owners outside the sporting industry who are investing in the veterinary care of older greyhounds, and this shift can also impact how these cases are managed. This review article aims to present the most recent literature on anaesthesia-induced hyperkalaemia in greyhounds and to raise awareness among veterinary professionals of the risk factors associated with its manifestation.

Greyhounds as anaesthesia candidates

Greyhounds are physically unique, having been bred primarily for athletic performance, and early empirical reports suggested that greyhounds responded differently to anaesthesia compared to other breeds8,9. Healthy greyhounds exhibit significant cardiovascular differences when compared with non-greyhounds, including larger hearts10, higher arterial blood pressure11 , higher frequency of low-grade benign systolic murmurs12, and elevated cardiac biomarkers, such as ProBNP13. Other clinicopathological distinctions include increased haematocrit, creatinine, and SDMA, as well as decreased leukocytes, platelets, potassium, sodium, and thyroid hormones14. Approximately 30 per cent of greyhounds experience delayed post-surgical bleeding due to hyperfibrinolysis and weaker clot kinetics15,16. They exhibit differences in drug metabolism, in part due to their low body fat composition; however, these differences mainly result from genetic variations in the breed’s hepatic Cytochrome P450 metabolic pathways17,18. Historically, malignant hyperthermia in greyhounds triggered by anaesthesia was reported in early published case studies19-22. However, literature does not support a genetic predisposition to malignant hyperthermia; instead, environmental factors, including stress, are more likely to contribute to its development23,24.

Anaesthesia-induced hyperkalaemia

Anaesthesia-induced hyperkalaemia has been reported in other species25,26, but it is a rare occurrence in dogs. A 2023 multi-centre retrospective clinical study reviewed data from cases over a seven-year period and identified only 13 cases of acute hyperkalaemia in non-greyhound dogs under anaesthesia27.

In contrast, an abstract presented at the AVA (Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists) conference in 2018 reported retrospective data on potassium measurements taken between 2013 and 2017 from greyhounds under anaesthesia. It found that 36 out of 95 (38 per cent) were hyperkalaemic (>5.6mmol), with 29 out of 36 (80 per cent) of the hyperkalaemic episodes occurring 120 minutes post-induction, and seven out of 36 (19 per cent) occurring within 90 minutes. All dogs received mechanical ventilation, yet hyperkalaemia occurred in the absence of respiratory or metabolic derangements. All dogs successfully recovered and were discharged from the hospital following recognition of hyperkalaemia and intervention4.

Six-year-old greyhound that suffered an episode of acute hyperkalaemia under GA. Author’s own image used with owner’s permission.

Published case studies in greyhounds

Published case studies of acute hyperkalaemia as a peri-anaesthetic complication in greyhounds involved healthy, non-racing, neutered greyhounds of both sexes, aged from 18 months to nine years. All cases reported anaesthetic durations exceeding 90 minutes.

McFadzean (2018)3 reported on a greyhound requiring diagnostic imaging due to suspected cervical spine pathology. The first episode of hyperkalaemia (7.89mmol/L) was identified 90 minutes into the anaesthetic, due to bradycardia, second-degree atrioventricular block, and hypotension. The patient’s potassium levels normalised 90 minutes after initiation of treatment with calcium gluconate to protect the myocardium, and glucose infusions and insulin to reduce blood potassium levels. The patient was recovered from anaesthesia prematurely but required further surgery and therefore underwent a further anaesthetic 45 hours later for cervical spine decompression surgery. Increasing potassium was observed once again, reaching a peak of 6.6mmol/L. Bradycardia with increased T-wave amplitude was noted on the electrocardiogram (ECG). Treatment was initiated with insulin and glucose infusions, the surgery was completed, and the dog recovered without complications.

Jones (2019)5 describes similar scenarios, where two different greyhounds underwent dental treatment years apart, where five separate general anaesthetics were described. All baseline potassium levels were normal, and increases in potassium under anaesthesia ranged between 7.2 and 7.7mmol/L and were identified between a timeline of 120 to 210 minutes. One incidence of bradycardia and two incidences of loss of P-waves were observed. In all instances, the dogs recovered without complications, with potassium levels returning to normal within hours of gaseous anaesthesia cessation, and no treatment other than intravenous saline boluses.

A case published in 2023 by Pye & Ward1 involved a young greyhound requiring anaesthesia for a forelimb fracture repair. A sudden drop in heart rate accompanied by loss of P-waves on the ECG occurred 150 minutes post-induction. Venous blood gas revealed a severe hyperkalaemia (8.2mmol/L). Initially, atropine was administered as an emergency intervention to treat bradycardia, followed by a calcium gluconate infusion. The patient was promptly recovered from inhalant anaesthesia, and a glucose infusion commenced in recovery. Potassium returned to within normal range within 70 minutes following recovery from anaesthesia. The patient recovered and was discharged without complications.

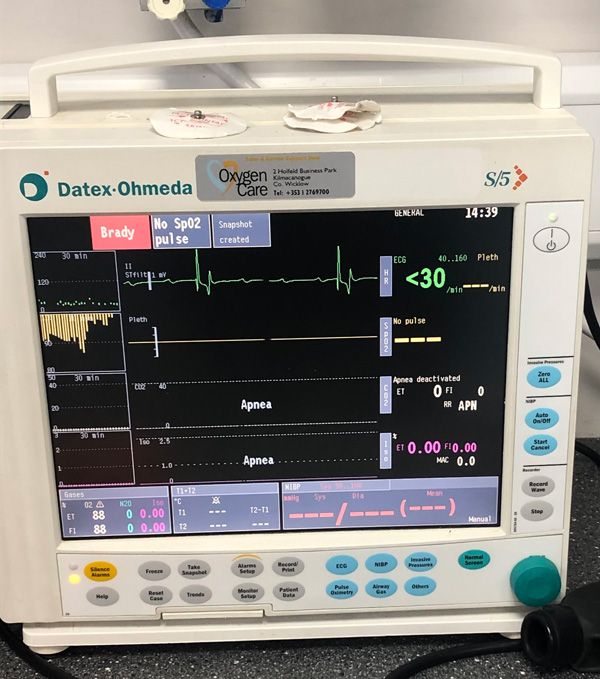

Same dog, image of ECG trace during hyperkalaemic episode under GA requiring intervention. Author’s own image used with owner’s permission.

The final case published by O’Neill (2024)2 was a young, healthy greyhound undergoing dental treatment. An acute bradycardia was observed 140 minutes post anaesthesia induction. A severe hyperkalaemia of 9.5mmol/L was recorded on a venous blood gas analysis. Calcium gluconate and atropine were administered as an emergency intervention, followed by glucose infusions and a 10mL/kg saline bolus. Tachycardia and ventricular tachycardia were observed during the recovery period. Intravenous lidocaine

was required to treat ventricular tachycardia, and oral gabapentin to reduce stress and anxiety. Potassium returned to normal 120 minutes following recovery from anaesthesia, and no further complications were observed.

Recent correspondence in a veterinary anaesthesia publication proposed a novel treatment for this form of hyperkalaemia in greyhounds28. The authors hypothesised that administering the inhalational β2-adrenoreceptor agonist salbutamol would reduce potassium levels by promoting potassium influx into cells through the drug’s activation of the Na/K-ATPase pump. Salbutamol has been suggested as an option for emergency treatment of hyperkalaemia in humans and has been shown to decrease potassium concentrations in normokalaemic dogs29. The authors tested this hypothesis in a healthy greyhound that developed hyperkalaemia while undergoing orthopaedic surgery. The hyperkalaemia was mild, and following the administration of salbutamol while the patient remained under general anaesthesia, potassium levels decreased over the subsequent 90 minutes (K+ 5.9 to 4.3).

Furthermore, a 2025 publication documenting the accidental aspiration of soda lime granules during routine general anaesthesia in a greyhound described how the patient required treatment for hyperkalaemia two hours after induction. Although this was not the primary focus of the case study, anaesthesia time was extended, and hyperkalaemia was observed, necessitating intervention30.

Aetiology

Greyhounds appear to be at higher risk of developing acute hyperkalaemia under inhalant anaesthesia, which highlights the need to consider hyperkalaemia as a differential diagnosis for bradycardia and arrhythmias that occur under anaesthesia in this breed.

Currently, the exact aetiology of this form of hyperkalaemia in greyhounds remains unclear.

Increased potassium load, decreased potassium excretion, or transcellular shift are the primary mechanisms which can lead to hyperkalaemia.

The use of alpha-2 agonists has been suggested as a potential contributor to hyperkalaemia due to their known effects on potassium homeostasis and their inhibition of insulin. However, alpha-2 agonists were not administered to every greyhound in the aforementioned case studies, nor to the majority of the 95 greyhounds included in the AVA 2018 abstract data. In addition, a study involving 24 greyhounds undergoing ovariohysterectomy described how they received a constant-rate infusion of dexmedetomidine alongside alfaxalone total intravenous anaesthesia for in excess of 90 minutes, and no signs of hyperkalaemia were reported in any dog31.

Currently, there is no definitive link between alpha-2 administration and acute hyperkalaemia during anaesthesia in greyhounds, nor is it clear whether these drugs contribute to its manifestation or exacerbation. However, further investigation into the impact of medications cannot be dismissed.

Respiratory depression and hypercapnia leading to respiratory acidosis, along with surgical tissue damage causing intracellular-extracellular potassium shifts, may be contributory factors. However, these are common occurrences during anaesthesia and surgery in dogs, and this phenomenon is far less frequently observed in other dog breeds.

Underlying renal impairment was not implicated in any of the greyhounds featured in the published greyhound case studies, and all patients were on intravenous fluid therapy during anaesthesia. However, the unique renal physiology of greyhounds may contribute to the aetiology of the condition. Prior research has shown that greyhounds exhibit lower resting aldosterone levels and reduced plasma renin activity ratios compared to non-greyhound dogs; the authors proposed that the downregulation of aldosterone levels is a natural response to the inherently lower sodium levels present in greyhounds32. Given that aldosterone plays a role in potassium excretion in the renal distal tubule and collecting duct, further research is necessary to ascertain the connection between these anomalies and potassium homeostasis under general anaesthesia in greyhounds. Previous studies in human patients and rats indicate that circulating aldosterone concentrations increase by 2.5 to five times in response to general anaesthesia, with significantly elevated levels in patients undergoing surgery33. The question remains whether a particular cohort of greyhounds has diminished adrenal capacity to respond to rising potassium levels and whether the genesis of this acute form of hyperkalaemia has a genetic basis or is triggered by a particular drug such as inhalant anaesthesia.

Future study

It would be reasonable to consider a familial component to this condition, and it has been suggested that only greyhounds from specific regions are affected. However, this hypothesis is problematic due to the large number of ex-racing greyhounds that have been exported from areas such as Ireland for re-homing, primarily across Europe and the United States, making it challenging to disentangle lineage origin.

Genome sequencing of greyhounds affected by hyperkalaemia under general anaesthesia is currently underway in the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine, aiming to identify a genetic contributor to the condition.

Another proposed study, suggested by a different group of researchers, that did not come to fruition, involved comparing serial measurements of aldosterone concentrations during anaesthesia and surgery in greyhound and non-greyhound dogs to investigate potential differences in serum aldosterone levels between the breeds in response to these conditions. Previously, this phenomenon in greyhounds may have been underdiagnosed due to the lack of routine anaesthetic monitoring, particularly ECG or electrolyte monitoring. The rise in reports of this form of hyperkalaemia is probably attributable to the increased number of complex procedures requiring longer general anaesthesia and the overall rise in greyhounds kept as companion animals.

To conclude, in the interest of greyhound welfare and based on the literature discussed, a strong recommendation is made for serial potassium monitoring in greyhounds undergoing anaesthesia for more than 60 minutes. Increased awareness and recognition of the condition are crucial, with routine ECG monitoring and the preparation of a treatment plan for prolonged anaesthesia advised.

- Pye E, Ward R. Hyperkalaemia in a Greyhound under general anaesthesia. Veterinary Record Case Reports. 2023;11(2).

- O’Neill AK. Hyperkalemia during prolonged anesthesia in a Greyhound. Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine. 2024;3908979(20).

- McFadzean W, Macfarlane P, Khenissi L, Murrell JC. Repeated hyperkalaemia during two separate episodes of general anaesthesia in a nine-year-old, female neutered greyhound. Veterinary Record Case Reports. 2018;6(3).

- Jones SJ, Mama KR, editors. Prevalence of hyperkalemia during anaesthesia in Greyhounds. Proceedings of the AVA Spring Meeting Grenada 2018.

- Jones SJ, Mama KR, Brock NK, Couto CG. Hyperkalemia during general anesthesia in two Greyhounds. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2019;254(11):1329-34.

- Kogika MM, Morais HAd. A quick reference on hyperkalemia. (Special Issue: Advances in fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base disorders.). Veterinary Clinics of North America, Small Animal Practice. 2017;47(2):223-8.

- Zaldivar-Lopez S, Marin LM, Iazbik MC, Westendorf-Stingle N, Hensley S, Couto CG. Clinical pathology of Greyhounds and other sighthounds. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2011;40(4):414-25.

- Robinson EP, Sams RA, Muir WW. Barbiturate anesthesia in greyhound and mixed-breed dogs: comparative cardiopulmonary effects, anesthetic effects, and recovery rates. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 1986;47(10):2105-12.

- Sams RA, Muir MW. Effects of phenobarbital on thiopental pharmacokinetics in Greyhounds. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 1988;49(2):245-9.

- Marin LM, Brown J, McBrien C, Baumwart R, Samii VF, Couto CG. Vertebral heart size in retired racing greyhounds. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound. 2007;48(4):332-4.

- Surman S, Couto CG, DiBartola SP, Chew DJ. Arterial blood pressure, proteinuria, and renal histopathology in clinically healthy retired racing Greyhounds. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2012;26(6):1320-9.

- Fabrizio F, Baumwart R, Iazbik MC, Meurs KM, Couto CG. Left basilar systolic murmur in retired racing Greyhounds. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2006;20(1):78-82.

- Couto KM, Iazbik MC, Marin LM, Zaldivar-Lopez S, Beal MJ, Gomez Ochoa P, et al. Plasma N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide concentration in healthy retired racing Greyhounds. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2015;44(3):405-9.

- Zaldívar-López S, Marín LM, Iazbik MC, Westendorf-Stingle N, Hensley S, Couto CG. Clinical pathology of Greyhounds and other sighthounds. Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2011;40(4):414-25.

- Chang J, Jandrey KE, Burges JW, Kent MS. Comparison of healthy blood donor Greyhounds and non-Greyhounds using a novel point-of-care viscoelastic coagulometer. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care. 2021;31(6):766-72.

- Lara-Garcia A, Couto CG, Iazbik MC, Brooks MB. Postoperative bleeding in retired racing greyhounds. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2008;22(3):525-33.

- Martinez SE, Andresen MC, Zhu Z-h, Papageorgiou I, Court MH. Pharmacogenomics of poor drug metabolism in greyhounds: cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2B11 genetic variation, breed distribution, and functional characterization. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1).

- Martinez SE, Pandey AV, Jimenez TEP, Zhu ZH, Court MH. Pharmacogenomics of poor drug metabolism in greyhounds: Canine P450 oxidoreductase genetic variation, breed heterogeneity, and functional characterization. Plos One. 2024;19(2).

- Bagshaw RJ, Cox RH, Knight DH, Detweiler DK. Malignant hyperthermia in a greyhound. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1978;172(1):61-2.

- Kirmayer AH, Klide AM, Purvance JE. Malignant hyperthermia in a dog: case report and review of the syndrome. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1984;185(9):978-82.

- Leary SL, Anderson LC, Manning PJ, Bache RJ, Zweber BA. Recurrent malignant hyperthermia in a Greyhound. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1983;182(5):521-2.

- Wright RP. Malignant hyperthermia in a greyhound: saving the patient from a fatal syndrome. Veterinary Medicine. 1987;82(10).

- Cosgrove SB, Eisele PH, Martucci RW, Gronert GA. Evaluation of Greyhound susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia using halothane-succinylcholine anesthesia and caffeine-halothane muscle contractures. Laboratory Animal Science. 1992;42(5):482-5.

- Perez Jimenez TE, Issaka Salia O, Neibergs HL, Zhu Z, Spoor E, Rider C, et al. Novel ryanodine receptor 1 (RYR1) missense gene variants in two pet dogs with fatal malignant hyperthermia identified by next-generation sequencing. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2025;52(1):8-18.

- Casoria V, Flaherty D, Auckburally A. Hyperkalaemia during two consecutive anaesthetics in an aggressive Bengal cat. Veterinary Record Case Reports. 2021;9(3).

- Hepps Keeney CM, Gorges MA, Gremling MM, Chinnadurai SK, Harrison TM. Hyperkalemia in Four Anesthetised Red Wolves (Canis Rufus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 2023;54(2):387-93.

- Tisotti T, Sanchez A, Nickell J, Smith CK, Hofmeister E. Retrospective evaluation of acute hyperkalemia of unknown origin during general anesthesia in dogs. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2023;50(2):129-35.

- Figurska M, Auckburally A, Torres-Cantó L. Use of inhaled salbutamol for the treatment of unanticipated hyperkalaemia during general anaesthesia in a Greyhound. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2025.

- Ogrodny A, Jaffey JA, Kreisler R, Acierno M, Jones T, Costa RS, et al. Effect of inhaled albuterol on whole blood potassium concentrations in dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2022;36(6):2002-8.

- Specht GA, Meyer R, Tearney C, Pratt C, Finke M, Meola DS. Anesthestic complication and endoscopic treatment of soda lime granule aspiration under inhalant general anesthesia in a greyhound. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2025(16):1-5.

- Quiros-Carmona S, Navarrete R, Dominguez JM, Granados MdM, Gomez-Villamandos RJ, Munoz-Rascon P, et al. A comparison of cardiopulmonary effects and anaesthetic requirements of two dexmedetomidine continuous rate infusions in alfaxalone-anaesthetized Greyhounds. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 2017;44(2):228-36.

- Martinez J, Kellogg C, Iazbik MC, Couto CG, Pressler BM, Hoepf TM, et al. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in Greyhounds and non-Greyhound dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2017;31(4):988-93.

- Oyama T, Taniguchi K, Jin T, Satone T, Kudo T. Effects of anaesthesia and surgery on plasma aldosterone concentration and renin activity in man. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1979;51(8):747-52.

Greyhounds have a lower baseline of serum potassium compared to non-greyhound dogs

- True

- False

2. Greyhounds have increased levels of thyroid hormones and leukocytes compared to non-greyhound dogs

- True

- False

3. ECG TRACES COMMONLY OBSERVED ACCOMPANYING HYPERKALAEMIA ARE:

- Bradycardia

- Loss of P-waves

- High amplitude T-waves

- All of the above

4. Hyperkalemia can be treated with:

- Insulin

- Glucose infusions

- Calcium gluconate

5. The average time period of published case studies in which greyhounds were identified as hyperkalaemic was:

- 30 minutes

- 60 minutes

- 90 minutes

ANSWERS: 1A; 2B; 3D; 4A and B; 5C.