Small animal - September 2019

Veterinary visits – the value of understanding feline behaviour

Vanessa Bourne MVB CertAVP(SAM-F) PGCertVetEd FHEA MRCVS, Beaumont Sainsbury Animal Hospital, Department of Clinical Science and Services, Royal Veterinary College, writes about how understanding feline behaviour can reduce stress before, during and after consultation

With an estimated 320,000 owned cats throughout Ireland (according to website, Statista), looking after our feline friends makes not only good welfare sense but also good financial sense. However, visiting the veterinary practice involves removing the patient from their normal environment and placing them in an unfamiliar one. This article highlights factors we should all be aware of in both the home and the clinic and provides solutions to the issues we may routinely face with feline patients. An optimal handling technique significantly reduces stress in cats making the visit more rewarding for patient, owner and clinician. Ultimately, this leads to an improvement in our examinations and diagnostic techniques, helping to increase job satisfaction for clinicians. Owners will be happier and it follows that income revenue will naturally increase.

Cats are easily stressed in the practice environment, which can have effects on both their health and behaviour. Behavioural changes associated with stress can cause problems for owners, affecting the human-animal bond. There is also a documented relationship between stress and disease (Amat et al, 2016).

Some reasons why owners may not seek veterinary attention for their feline pets include concerns over the cat’s stress and fear, and the practical difficulties in transporting the cat to the practice (Vogt et al, 2010). Education of clients with regards to the behavioural characteristics of the cat will help them to learn to interpret behaviours from the animal’s perspective. Cats are not a naturally social species and are highly territorial. This means that they feel both vulnerable and threatened when removed from their normal environment (Sparkes, 2013). Contact with unfamiliar people and animals, previous negative experiences, physical restraint and pain reduce their normal active behavioural response (Roden et al, 2011). Simple changes can dramatically improve the practice-patient interaction, making the experience better for staff, pet and owner. This increases client bonding to the practice as well as making feline welfare a priority.

A large part of the article is derived from the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) and International Society of Feline Medicine (ISFM) feline-friendly handling guidelines by Roden et al 2011, published in the Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. This article is freely available from a variety of sources and can easily be downloaded and distributed to team members as an excellent point of reference. Adapting these guidelines to each individual cat can lead to:

- Reduced pain and fear for the patient;

- Reinforced vet-client-patient bond, trust and confidence and therefore improved lifelong medical care for the cat;

- Improved efficiency, productivity and satisfaction for the veterinary team;

- Increased client compliance;

- Early detection of medical and behavioural problems;

- Fewer injuries to clients and veterinary team; and

- Reduced anxiety for the client.

Feline behaviours relevant to the home environment

In addition, veterinary professionals can help educate owners regarding their feline pet’s environmental needs. Signs of stress in cats are often subtle and difficult to recognise, frequently resulting from the cat’s needs not being met, which is often due to a lack of understanding by the owner. This has resulted in an increase in stress-associated disease such as lower urinary tract disease, vomiting, diarrhoea or anorexia (Pachel, 2014) and obesity associated diabetes mellitus (Ellis et al, 2013). It has only been recently that our understanding of the aetiology and pathogenesis of clinical signs for some disorders has expanded to recognise the variety of vulnerability factors that may result in a susceptible individual, and the range of features that might constitute a provocative environment (Buffington et al, 2014).

The AAFP and ISFM developed The Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines, which are organised around five primary concepts (pillars) that provide the framework for a healthy feline environment (Ellis et al, 2013).

Five pillars of a healthy feline environment

Pillar 1: Provide a safe place.

Pillar 2: Provide multiple and separated key environmental resources: food, water, toileting areas, scratching areas, play areas and resting or sleeping areas. The number of each resource should equal the number of cats in the household plus one extra.

Pillar 3: Provide opportunity for play and predatory behaviour.

Pillar 4: Provide positive, consistent and predictable human-cat social interaction.

Pillar 5: Provide an environment that respects the importance of the cat’s sense of smell.

Feline behaviours relevant to the clinic or hospital environment

Cats are solitary animals, generally avoiding confrontation. Avoidance or hiding is often the initial response with fighting occurring as a last resort. Allowing cats to remain protected and hidden while at a veterinary practice can therefore improve handling. If we can recognise signs of anxiety, we can take steps to prevent escalation to fear aggression. Ear position, body posture, facial and eye changes and tail movements are helpful indicators. Increased sweat may be produced from the paws. Vocalisation may occur in the form of distress-meowing to growling, hissing or spitting. Cats lack techniques to resolve conflict through appeasement so resort to freeze, flee, fight or displacement behaviours. Both fear-induced withdrawal and aggression make diagnosis and treatment difficult. In addition, stress can impair recovery from illness or injury (Carney et al, 2012).

Unfamiliar circumstances that cats encounter in veterinary clinics may give rise to anxiety and fear. These suppress normal behaviours (such as rest and feeding), and increase vigilance, hiding and dysfunctional signs, such as anorexia, vomiting and diarrhoea or lack of elimination. Physiologic responses to stress include hyperglycaemia, decreased serum potassium concentrations, elevated serum creatinine phosphokinase concentrations, lymphopenia, neutrophilia, unpredictable response to sedation and anesthesia, immunosuppression, hypertension and cardiac murmurs (Carney et al, 2012). These changes can complicate treatment of feline patients and create confusion with diagnosis.

Preparation for the veterinary visit

Minimising stress before arrival at the veterinary clinic is likely to help improve the consultation, as the patient will hopefully be more compliant and relaxed than if presented to a clinic environment following a stressful journey.

Making the time to accustom the cat to travel and handling can reduce the stress of veterinary visits long-term. The veterinary team and client need to work together to provide positive veterinary experiences. According to Roden et al, 2011 this can be done by:

- Rehearsal of visits to the practice using positive rewards to introduce the cat to the practice, being around other cats and people;

- Offering client education classes;

- Rehearsal of clinical examinations at home. Owners can perform simple examinations at home using positive reinforcement, eg. handling paws, looking into ears, opening of mouth;

- Understanding the effect of our own anxiety on the cat;

- Helping the cat get used to the carrier, including taking occasional short car journeys; and

- Proceeding at the cat’s pace and being aware of the cat’s responses, using rewards where needed.

Getting ready to leave the home

Leaving the carrier permanently in the environment with familiar bedding allows the cat to become used to its presence and possibly utilise it as a safe place. This is much less stressful than presenting a carrier with which the cat only associates transport and stress, that smells unfamiliar, has been stored in a garage or shed or has been used to transport other animals in (Roden et al, 2011). Some consideration should be given to the carrier itself, which needs to provide both safety and support for the cat during use. They need to be easy to use, sturdy, secure, easy for the client to carry and quiet to open. Some cats may enjoy visual stimulus while others prefer to hide so awareness of preferences by the owner is needed. The design should permit easy removal of the cat or have a removable top and front to allow examination of the cat within the carrier (Roden et al, 2011).

Using a synthetic feline facial pheromone (FFP) analog spray 15-30 minutes before transport can help calm the patient. Feliway (Ceva Animal Health) has been shown to facilitate cats’ habituation to new environments and is therefore useful in hospitalised cats and when cats are transported (Pereira et al 2015). The pheromone needs to be applied sufficiently early in order to take effect and to allow the alcoholic solvent to evaporate before introducing the cat to the area. Feliway will typically last four to five hours before reapplication is needed. In addition, to using on the interior of the carrier and bedding, FFP analog sprays can be used on a blanket or towel, which is then placed over the carrier. As well as exposing the cat to the pheromones, the towel also blocks visual stimuli.

If the cat does not voluntarily enter the carrier at home, then placing the carrier in a small room with few hiding opportunities may encourage the cat to select the carrier. Usage of FFP analog sprays in the carrier beforehand can help reduce stress, along with placing familiar bedding, toys or food inside the carrier.

It is important to select a carrier that is easy for the owner to carry, as excess knocking of the carrier will cause stress during the journey. They need to ensure the carrier is secured within the vehicle as moving carriers can frighten the cat (Roden et al 2011).

The scope of this article does not cover in depth the use of pharmacological agents to provide sedation for transport and consultations. However, it is worth acknowledging the recent interest in the use of gabapentin to reduce anxiety in fearful animals. Pankratz et al (2018) determined that 50mg or 100mg of gabapentin produced a significant reduction in fear responses without significant sedation in a population of feral cats undergoing a TNR programme. The author has used various dosages ranging from 25-100mg of gabapentin in a number of feline patients before veterinary visits with good success.

Preparing the practice environment

Key considerations for creating a cat-friendly environment are listed as follows:

- Manage odours. Cats’ sensitive sense of smell drives many of their behavioural responses. Some odours (eg. disinfectant, blood, deodorant) may cause anxiety and fear. Ensure all surfaces are clean and areas ventilated;

- Consider using a synthetic feline facial pheromone analog. Cats may benefit from diffusers placed throughout the hospital and a spray used 30 minutes in advance on material used for bedding and handling; and

- Manage visual and auditory input. Keep other patients away from the cat’s line of vision. Bright or constant light can be stressful. As cats perceive light in greater abundance than humans, using soft lighting (eg. 60W bulbs) may be helpful. Speaking quietly and avoiding excess chatter can help patients stay calm.

Preparation of the practice environment should include all areas that the patient may visit (including the car parking area and distance of this from the practice). Waiting times should be minimised. Where possible, cat appointments should be made for quieter periods of the day and cat and other species appointments should be at different times. There should be provision of a separate feline waiting area. Provide level tables to place the carrier on so the cat is not on the floor. Cover the carrier with a familiar towel if possible or have towels available in the reception area to use. Ensure that towels are not swapped between cats as this will allow scent signals to transfer between patients (in addition to the risk of transferred diseases).

A minimum of one exam room should be dedicated to cats only and should provide a number of surfaces where the cat can make themselves comfortable, eg. chair, windowsill. Conducting the exam wherever the cat appears most comfortable can improve handling. Provision of a variety of food treats, disposable toys or catnip can be beneficial.

Cat-only wards should be provided, separate from other patients. The cage should be large enough to accommodate the carrier and for the litter box to be away from food, bedding and water. Alternatively, provision of a cardboard box or other safe haven with hiding and perching areas can be supplied. Side by side cages are preferable to cages facing each other as this reduces visual stimulus. Mid level or higher cages are preferable to those close to the floor. The temperature and noise level should be controlled; fibreglass cages are warmer, less reflective and quieter than stainless steel. Studies have shown that classical music has been shown to increase behaviours associated with relaxation in animals (Herron and Shreyer, 2014). Toys or bedding from home can reduce stress and consideration to the cat’s litter and typical diet should be given. The type of litter tray should also be considered; elderly patients may benefit from a flat litter tray to aid entry and exit.

Interaction with the feline patient in the veterinary practice

Our body language and attitude can affect a patient’s stress levels. Greet cats and owners with moderated body language and voice. Management of owners is needed, as they are frequently keen to get the cat out of the box quickly and may speak loudly. Be aware of any special requirements eg. soft surfaces for patients with arthritis. Be prepared with equipment readily to hand to minimise length of exam and noise associated with looking for items. Use a slow approach with a calm, positive demeanour. A direct, frontal approach may appear threatening.

Open the carrier door while taking the history so the patient can choose whether to venture out. If the patient is still in the carrier once the history has been taken, quietly remove the top and door if possible, and perform as much of the examination as possible within the carrier. A towel could be placed around or over the patient to provide additional cover during the exam.

If the carrier cannot be disassembled, avoid grabbing the cat or tipping the carrier. Reach in and support the back end to encourage the cat to move forward.

A variety of handling techniques can be utilised for each patient (Vogt et al, 2010; Roden et al, 2011). These include:

- Usage of towels or anti-slip mats under the cat or ideally bedding from the carrier;

- Examine the cat in a lap with the cat facing towards the client and away from the examiner, using your body and arm to support the cat;

- Allow the cat to maintain its chosen position;

- Vary your touch with the cat’s response. Massaging the cranial aspect of the ears or between the eyes can help calm the cat. Most cats prefer the head and neck for physical touch and may become upset or aggressive if petted in other areas;

- Swaddle the cat in a towel or cover the head with a towel;

- Wherever possible, perform procedures in the exam room;

- Avoid direct eye contact;

- Move slowly and deliberately, minimising hand gestures. Use quiet voices and encourage the owner to do the same. Avoid loud noises or ambient sounds that may mimic hissing (eg. whispering);

- Put yourself on the same level as the cat; do not loom above or over the animal. Approach from the side;

- If the cat is anxious, return it to the carrier as soon as possible and continue to talk to the owner while the cat is in its safe place; and

- If medical procedures are needed, begin with those less stressful or invasive.

If the cat exhibits signs of fear, slow down or take a break from handling. Signs may first manifest as changes in ear position, eyes and facial expression, body posture, paw sweating and tail movement (Carney et al 2012). Patients may try to escape or freeze in position. If steps are not taken to reduce fear and anxiety, escalation of behaviour may occur. This can include vocalisation, biting and scratching. Avoiding excessive restraint of a fearful patient is important. Adopting a heavy-handed approach is very likely to cause problems for future visits as well as being distressing for the patient and owner. It is also likely to be an unsuccessful approach and merely exacerbate or escalate the patient’s behaviour. Allowing the patient a break from handling may be sufficient to reduce anxiety sufficiently enough to continue the examination or procedure. If pain is suspected to be a contributing factor, providing analgesia first may allow for a successful re-examination later. If the examination or procedure is elective, it may be appropriate to stop and formulate a suitable plan to address fear with the owner, rescheduling for a later date.

Regardless of our efforts, some patients may require sedation for examination. If the patient is already known to be fearful, administration of 50-100mg of gabapentin prior to the pet leaving the home may be sufficient to allow examination. If the cat cannot be handled safely, intramuscular sedation may be required. Subcutaneous administration results in unpredictable effects. Placing the patient in a crush cage can allow for rapid injection and protect against staff or patient injury. Consideration of comorbidities is important when selecting sedative agents, as some may be subclinical (for example, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) or undiagnosed. If pain is suspected or known to be present, a suitable agent should be chosen to provide analgesia.

In some cases, an opioid alone may be sufficient to sedate a patient enough to allow examination (for example. butorphanol 0.2-0.5mg/kg, methadone 0.1-0.3mg/kg or buprenorphine 0.02-0.03mg/kg). Butorphanol generally provides a better-quality sedation than other opioids when given alone, but is not suitable for the provision of analgesia. There are numerous intramuscular combinations (Robertson et al, 2018) available, including:

Opioid (butorphanol, buprenorphine or methadone) + medetomidine (0.005-0.02mg/kg);

Opioid + medetomidine + ketamine (2-3mg/kg);

Opioid + medetomidine + midazolam (0.05-0.2mg/kg);

Opioid + medetomidine + alfaxalone (1-2mg/kg);

Opioid + alfaxalone (2-3mg/kg);

Opioid + midazolam (0.2-0.3mg/kg);

Medetomidine + alfaxalone (1-2mg/kg); and

Midazolam (0.2-0.3mg/kg) + ketamine (2.5-5mg/kg).

Going home after a veterinary visit

Despite our best efforts, some degree of stress is unavoidable in all but the most relaxed of cats. Stress can reduce feed intake and increases the risk of cats displaying unwanted behaviours. These could take the form of aggression, compulsive behaviour or inappropriate elimination (Amat el al 2016).

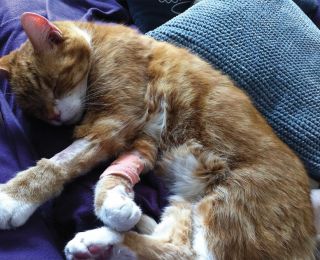

When cats return home, they may carry unfamiliar materials eg. bandages or odours from the practice. This may create problems with other cats in the home, causing stress to all parties. Using familiar bedding and synthetic FFP analogs can help reduce this as well as adopting a passive approach when bringing the cat home, ie. not forcing the cats together.

Environmental enrichment and correct provision of key resources can significantly reduce conflict (Rochlitz 1999). There should be the same number of resources as cats plus one extra. Resources include food and water bowls, litter trays and safe places to rest or hide. Provision of suitable safe places can be used for cats to rest peacefully or retreat to, allowing the cat to exert control over their surroundings and hence reducing stress (Amat et al 2016).

Where there are multiple cats in the household and a more severe conflict occurs, a reintroduction protocol could be used (Amat et al 2016). The protocol is divided into three phases: olfactory habituation, visual habituation and direct contact habituation. The duration of each part is variable, depending on the severity of the conflict. Initially, each cat is confined to a different part of the household and all key resources are provided in both areas. Each cat is then moved to the other area so that both animals are exposed to the other cat’s odour. Using a piece of cloth, the secretion of the facial gland of each cat can be applied to the cheeks of the other cat. When both cats appear relaxed, visual contact between them is provided when they are engaged in a pleasant activity. They are otherwise kept separated and the duration of the visual contact sessions is gradually increased. Finally, in the last phase, the cats are fully reintroduced.

In summary, optimal cat handling techniques and adjustment of the practice wherever practically possible have significant benefits in terms of patient stress and improved client bonding. Serious injury can occur to staff members and owners through inappropriate handling. Trust and bonding can be irreparably broken during a single examination by unsympathetic handling. Therefore, it makes both good ethical and financial sense to improve feline handling in the veterinary practice.

Amat M et al. Stress in owned cats: behavioural changes and welfare implications. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2016; 18: 577-586

Buffington CA et al. From FUS to Pandora syndrome. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2014; 16: 385-394

Carney HC et al. (2012). AAFP and ISFM feline-friendly nursing care guidelines. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 14, pp. 337-349.

Ellis SLH et al. AAFP and ISFM feline environmental needs guidelines. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2012; 15: 219-230

Herron ME, Shreyer T. The pet-friendly veterinary practice: a guide for practitioners. Veterinary Clinics of North America 2014; 44: 451-481

Pachel CL. Intercat aggression: restoring harmony in the home. Veterinary Clinics of North America 2014; 44: 565-579

Pankratz KE et al. Use of single-dose oral gabapentin to attenuate fear responses in cage-trap confined community cats: a double-blind, placebo-controlled field trial. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2018; 20: 535-543

Pereira JS et al. (2015) Improving the feline veterinary consultation: the usefulness of Feliway spray in reducing cats’ stress. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2015; 18: 959-964

Robertson SA et al. (2018) AAFP Feline anaesthesia guidelines. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2018; 20: 602-634

Rochlitz I. Recommendations for the housing of cats in the home, in catteries and animal shelters, in laboratories and in veterinary surgeries. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 1999; 1: 181-191

Roden, I et al. AAFP and ISFM feline-friendly handling guidelines. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2011; 13: 364-375

Sparkes A. Developing cat-friendly clinics. In Practice 2013; 35: 212-215

Vogt AH et al (2010) AAFP and AAHA feline life stage guidelines. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 2010; 12: 43-54

1. Signs of anxiety in feline patients include:

a. Changes in ear position

B. Sweat production from paws

C. Vocalisation

D. All of the above

2. Physiological responses to stress include:

a. Hyperglycaemia, lymphopenia, neutrophilia, decreased serum potassium concentrations, hypertension

B. Hypoglycaemia, lymphopenia, neutrophilia, increased serum potassium concentrations, hypertension

C. Hyperglycaemia, lymphocytosis, neutropenia, decreased serum potassium concentrations, hypertension

D. Hypoglycaemia, lymphocytosis, neutropenia, increased serum potassium concentrations, hypotension

3. Key environmental resources include:

a. Food and water bowls

B. Litter trays

C. Resting or sleeping areas

D. Outside space

e. All of the above

f. A B and C

G. A B and D

4. How many of each key resource should be provided?

a. One per cat

B. One per household

C. One per cat plus one extra

D. One per two cats

Answers: 1 d; 2 A; 3 f; 4 c