Bovine abortion: causes and diagnosis

The recent Schmallenberg outbreak has alerted us all to the devastating effects of infections during pregnancy causing abortions, stillbirths and deformed calves. In this article John F Mee* PhD MVM MVB Dip ECBHM FRCVS, Moorepark Research Centre, Teagasc provides an update on the multiple causes of abortion and the latest laboratory tests aimed at improving diagnosis rates for veterinary practitioners and their clients

*Corresponding author: john.mee@teagasc.

While abortion is technically defined as pregnancy loss between 42 and 260d of gestation, losses prior to 120d are rarely observed, though of greater magnitude. Using this gestational threshold (>120d), an ‘observable abortion’ rate of <2 per cent could be expected in a ‘normal’ herd. Approximately half (45 per cent) of laboratory-submitted abortion cases have a diagnosis. Of these, the most common causes of sporadic abortions in dairy and suckler herds are Trueperella pyogenes and Bacillus licheniformis, respectively, while the most common cause of abortion outbreaks is Neospora caninum. Current adoption of PCR and second- and third-generation sequencing technologies and detection of recessive lethal alleles will increase future abortion diagnosis rates.

Introduction

In Ireland, it is a legal requirement to notify DAFM of any case of abortion in a bovine animal (SI 114 of 1991). Additionally, as brucellosis (Brucella abortus) is a notifiable disease in Ireland (though officially eradicated in 2009) anyone who suspects that an animal may have the disease, e.g., aborts, is also legally obliged to notify DAFM (SI 130 of 2016).

Clients may often adopt a fatalistic attitude to abortion – ‘where there is livestock there is deadstock’, a form of learned helplessness. This is particularly true for sporadic abortions. However, recent national and international advances in laboratory diagnostics indicate that we should recalibrate our expectations regarding diagnosis of abortion in cattle. So, to facilitate this process this article addresses five common questions about bovine abortion with emphasis on potential causes and case investigation by veterinary practitioners.

1. What do you define as an abortion?

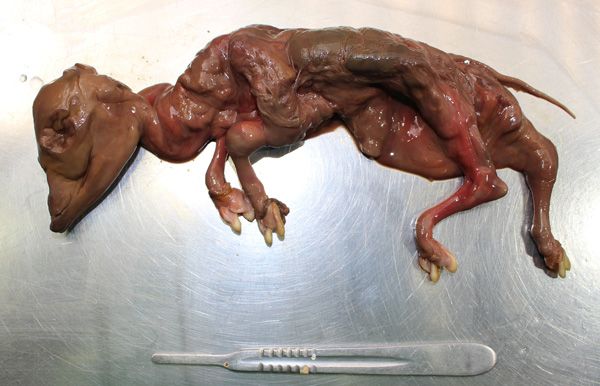

While it is traditional to define bovine abortion as expulsion of a dead or non-independently viable live foetus and its adnexa between 42 and 260 days of gestation (Mee, 2023) this is a purely academic case definition. In practice today (dairy) cows are often scanned ~30 days after last service and maybe again at ~60 days and/or palpated in late pregnancy if there is suspicion of abortion, e.g., oestrus observed. Thus, ‘abortion’ may be defined in practice as circumstantial evidence (by farmer - return to oestrus) or proof (by vet - none or dead foetus on scan) of pregnancy failure after pregnancy confirmation. This field definition can obviously lead to wide variation in (poorly comparable) estimates of abortion rates. For example, data from vets (n=77) in four countries (Ireland, UK, Italy, Canada) surveyed at conferences showed that the most used case definition (43 per cent) was expulsion of a preterm non-viable foetus, without specification of gestational age. Where age was specified, the most common (36 per cent) threshold was <260 days. As pregnancy loss rates are much higher in the first trimester (Figure 1), but these losses are not always observable [as confirmed by very low submission rates of foetuses <120d (size of a cat, CRL ~30cm) to diagnostic laboratories], it has been suggested that a practical definition of ‘observable abortion’ is foetal loss between 120 and 260d of gestation (Mee, 2021). While both visual markers (Agerholm et al, 2023) and simple morphological measurements (e.g., crown-rump length), (Jawor and Mee, 2025) may be used to estimate foetal age, neither method is day-precise, but adequate to estimate approximate month of gestation.

Figure 1. Early aborted foetuses (abort in Sep-Nov in spring-calving herds) are rarely submitted for laboratory examination.

2. How many abortions would you expect in a ‘normal’ herd?

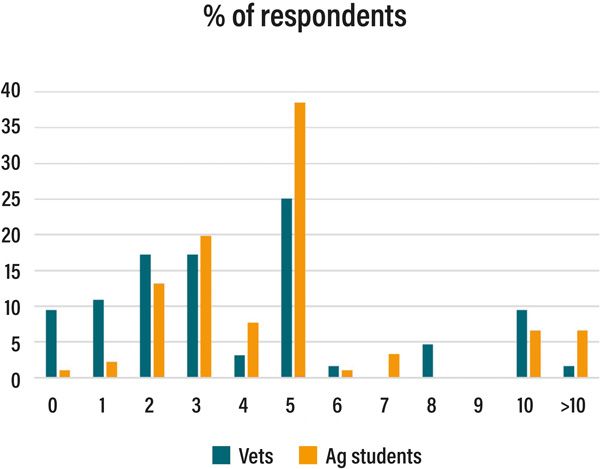

With our average dairy and suckler herd sizes of ~100 and 15 cows, respectively, it may be possible to use a per cent threshold value for dairy herds but not in small (suckler) herds. In the absence of accurate data on national herd-level abortion rates, the opinions of farmers and their vets are more commonly used to decide on the threshold of acceptance/intervention. Data from vets (n=77) in four countries (Ireland, UK, Italy, Canada) and Irish agricultural students (n=91) showed that both groups had digit bias towards >5 per cent as an investigative threshold (Figure 2) but most vets (63 per cent) and ag. students (84 per cent) used a threshold of >3 per cent. In the UK, dairy and suckler farmers reported thresholds of 2-5 and >0 per cent, respectively, (Clothier et al, 2020). In contrast, an intervention level of 10 per cent has been recommended for dairy herds in the USA; where early abortions are included (e.g., following confirmed pregnancy scan at ~30-day), intervention thresholds will naturally be much higher.

The most recent estimates of animal-level early abortion rates from meta-analyses are 9 per cent (45-90 days) in dairy cows (Albaaj et al, 2023) and 6 per cent (32-100 days) in beef cows (Reesce et al, 2020). Estimates of animal-level foetal abortion rates in dairy cows have recently been reviewed with an average of ~12 per cent estimated (42-260 days), (Wijma et al, 2022). Estimates of animal-level dairy mid-late term abortion rates are much lower varying between 1.2 per cent (>152d and <251d), (Neupane et al, 2023) and 1.7 per cent (120-259d) (Mee, 1992).

These data confirm that if ‘abortion’ includes early pregnancy losses then a high threshold of ‘normal’ (~10 per cent) can be applied but if ‘abortion’ only includes mid-late pregnancy losses then a lower ’normal’ threshold (~2 per cent) can be applied. However, in our seasonal-calving systems a temporal cluster of abortion cases (an outbreak/’storm’) often warrants investigation even if the annualised prevalence is below this suggested threshold.

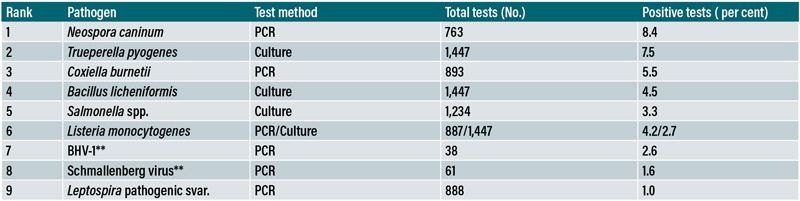

Table 1: Infectious agents detected in bovine foetal material in the regional veterinary laboratories in 2023.

*Many other infections, of unclear clinical significance, were also detected; detection with lesions is convincing of causation but absence of detection does not rule out infection.

**Note the limited number of total (selected) tests.

3. What’s the best way to deal with a call to an aborted cow?

When a farmer reports an abortion, the standard operating procedure (SOP) should include advise on potential zoonotic risks (and to wear appropriate PPE), to isolate the affected animal, clean/disinfect the abortion site, collect the foetoplacental material into biosecure, scavenger-proof storage, (biopsy)-tag the foetus and submit all aborted material to the regional vet lab (RVL). The farm visit abortion SOP should include collection of a clinical history, clinical examination (and of cohorts), maternal blood sample (from aborted animal and cohorts) and review of existing biosecurity practices (e.g., vaccination regime). Knowing that less than 50 per cent of abortions will have a laboratory diagnosis, enquiry about potential on-farm risk factors which cannot be detected by the lab may prove fruitful, e.g., recent stress (drying off, hoof trimming, ‘crushing’), illness (postparturient disorders, previous abortion, mastitis, lameness), recent loss in BCS, short CCI and twinning (Mee, 2023).

Figure 2: Investigative thresholds (at or above per cent) for abortion used by vets and agricultural students.

4. What are the most common causes of abortions?

The data in Table 1 show the latest available results on the detection rate of infectious agents likely to cause abortion in foetal material submitted to the six RVLs (Hayes, 2024). The overall infectious diagnosis rate was 45 per cent, similar to rates internationally (Mee, 2023). This means that the majority of abortions are caused by non-infectious factors. Of the top 10 infections listed, N. caninum, Coxiella burnetii and Salmonella Dublin are more likely to cause abortion outbreaks while the remainder cause sporadic abortions. When these data were disaggregated by enterprise type, certain bacteria were more likely to be detected in dairy (T. pyogenes, S. Dublin) than in suckler herds; and in suckler (B. licheniformis) than in dairy herds.

Similar associations have been found in UK and EU data. Notable features of these data are:

- C. burnetii has been reported in abortion diagnostics for the first time; and,

- both salmonella and leptospiral infection have a low prevalence in foetal material.

The former reflects the recent introduction of PCR testing and the latter two, perhaps, widespread vaccination. It should be noted that some pathogens are more likely to be detected in the foetus (e.g., T. pyogenes) and others in the placenta (e.g., S. Dublin) hence the importance of always submitting both (Hayes et al, 2023); currently the placenta accompanies the foetus in ~25 per cent of submissions. Overall, these findings suggest that the most common diagnosed causes of sporadic abortions in dairy and suckler herds are T. pyogenes and B. licheniformis, respectively, while the most common cause of abortion outbreaks is N. caninum. However, the majority of abortions are non-infectious in origin.

5. How can we improve the abortion diagnosis rate?

If we accept that most abortions are non-infectious in origin (diagnosis-not-reached – DNR), then we need to improve our DNR diagnosis rate. However, non-infection diagnoses are not likely to be made in veterinary diagnostic labs, which specialise in infectious diagnoses. The best hope here for the future is the increasing detection of recessive lethal alleles in embryonic and early foetal mortality as exemplified by the sire Pawnee Farm Animal Chief which has been linked to over half a million abortions worldwide.

Attempts to improve the abortion infectious diagnosis rate are ongoing nationally and internationally. For example, in recent years DAFM and commercial vet labs (e.g., FarmLab Diagnostics) have introduced abortifacient PCR screening tests (Anaplasma phagocytophilia, Bovine herpesvirsus-4, Campylobacter fetus, Chlamydophila, C. burnetii, Leptospira, Neospora and Salmonella). For the first time, these tests generated results on these common and not so common abortifacients in Irish foetal material.

Additionally, research is being conducted on difficult-to-diagnose pathogens through samples submitted to the RVLs (Hayes et al, 2023). In parallel, research has started using metagenomic next generation sequencing (NGS) to identify Pathogen Y (viral foetopathogens not identified by routine diagnostic methods) in aborted material as part of the One Health: All Ireland for European Surveillance (OH-ALLIES) project. Related diagnostics (nanopore sequencing) have recently been introduced in Belgium and the Netherlands for bovine abortion diagnostics (PathoSense). And in Denmark, microbiome analysis (16S and 18S MA; non-virome) is now routinely used to assist in diagnosis of bovine abortions. All of these initiatives are likely to continue the current trend of increasing abortion diagnosis rates internationally.

Agerholm, J. S., Dahl, M., Herskin, M., & Nielsen, S. S. (2023). Forensic age assessment of late-term bovine fetuses. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 65(1), 27.

Albaaj, A, Durocher, J, LeBlanc, SJ, Dufour, S. (2023) Meta-analysis of the incidence of pregnancy losses in dairy cows at different stages to 90 days of gestation. Journal of Dairy Science Communications, 4:144-148.

Clothier G, Wapenaar W, Kenny E, Windham E (2020) Farmers’ and veterinary surgeons’ knowledge, perceptions and attitudes towards cattle abortion investigations in the UK. Veterinary Record, doi: 10.1136/vr.105921.

Hayes, C. (2024) Bovine abortion. All-Island Animal Disease Surveillance Report, 2023, p. 14-17.

Hayes C, Mee, J.F., McAloon C, Markey B, Casey M, Innes E, Sanchez C (2023). Prevalence of bacterial and fungal abortifacient pathogens in bovine foetuses and placentae – a national study. Animal - Science Proceedings 14, 431–548.

Jawor, P. and Mee, J.F. (2025) Use of morphometry to estimate dairy bovine foetal age at abortion and stillbirth. Journal fur Reproduktionsmedizin und Endokrinologie, 22 (1), 10-11.

Mee, J.F. (2023). Invited review: Bovine abortion—Incidence, risk factors and causes. Reproduction in Domestic Animals, 00, 1–11.

Mee, J.F. (2021). Bovine abortion. In. Bovine Prenatal, Perinatal and Neonatal Medicine, Hungarian Association for Buiatrics, Budapest, p. 58-66.

Mee, J.F. (1992). Epidemiology of abortion in Irish dairy cattle on six research farms. Irish Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, 31: 13-21.

Neupane M, Hutchison JL, Cole JB, Van Tassell CP, VanRaden PM (2023). Genomic evaluation of late-term abortion in cows recorded through Dairy Herd Improvement test plans. Journal of Dairy Science Communications, 4: 354-357.

Reese ST, Franco GA, Poole RK, Hood R, Montero LF, Oliveira Filho RV, Cook RF, Pohler KG (2020). Pregnancy loss in beef cattle: A meta-analysis. Animal Reproduction Science, 212:106251.

Wijma R, Weigel DJ, Vukasinovic N, Gonzalez-Peña D, McGovern SP, Fessenden BC, McNeel AK, Di Croce FA (2022). Genomic prediction for abortion in lactating Holstein dairy cows. Animals 12: 2079.

1. DEFINE ABORTION:

- Foetal loss between 0 and 42d of gestation

- Foetal loss between 42 and 260d of gestation

- Foetal loss after 260d of gestation

- Foetal loss caused by an infection

2. WHAT IS A NORMAL MID-LATE TERM ABORTION RATE?

- <10 per cent

- 2-10 per cent

- <2 per cent

- 0 per cent

3. ADVICE TO A FARMER WITH AN ABORTED COW SHOULD INCLUDE:

- Zoonosis advice

- Isolate cow and disinfect abortion site

- Biopsy tag foetus and submit foetus/placenta to the lab

- All of the above

4. THE MOST COMMON CAUSE OF A SPORADIC ABORTION IN A DAIRY HERD IS:

- Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BHV-1)

- Mycotoxins

- Congenital defects

- Trueperella pyogenes

5. THE MOST COMMON CAUSE OF AN ABORTION OUTBREAK IS:

- Salmonella Dublin

- Schmallenberg virus

- Neospora caninum

- BHV-4

ANSWERS: 1B; 2C; 3D; 4D; 5C.