Motivational interviewing in veterinary practice

Alison Burrell MSc CPsychol Ps SI, Chartered Health Psychologist at Animal Health Ireland (AHI) and Laura Gribben BSc MSci, PhD student at Queen’s University Belfast and Teagasc Walsh Scholar, summarise key components of motivational interviewing, as outlined in the book ‘Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change’ by psychologists William Miller and Stephen Rollnick, and its use within the veterinary profession to have effective conversations about change

Previous articles for the Veterinary Ireland Journal have outlined the critical role of the veterinary practitioner as an advocate for behavioural change in relation to antimicrobial resistance and herd health planning (Gribben and Burrell, 2023; Regan and Burrell, 2021). Within the realm of preventative veterinary medicine and herd health planning consults, evidence-based communication strategies which draw on psychological theory and practice have been shown to improve shared decision-making and collaboration between veterinary practitioners and their clients (Bard et al, 2022). In this article, we will describe the relational and technical components of motivational interviewing.

The term ‘motivational interviewing’ (MI) might suggest images of someone standing on a stage with a handsfree microphone and an inspirational speech, something which it is not. In short, MI is a collaborative conversation style reflecting person-centred care and is used to elicit and strengthen a person’s own, intrinsic motivation to change. It is used by those working in a helping profession such as counsellors, social workers, doctors, teachers, physiotherapists, psychologists and probation officers.

Miller and Rollnick (2013) give the example of a healthcare professional who is supporting a patient to respond to a chronic disease diagnosis. This patient’s future health, quality of life and indeed life expectancy may be determined by their behaviour and lifestyle. The kind of helping conversation that the healthcare professional might have with their patient in this situation can be described as being on a continuum of communication styles.

On one side of this continuum is a ‘directing’ style of communication – the practitioner tells the patient what to do and how to do it and this requires adherence and compliance from the patient. On the other side of this communication continuum is ‘following’ – the practitioner merely seeks to understand and does not give any of their own views or advice at all. Motivational interviewing sits in between these two approaches, in a ‘guiding’ style of communication.

Millner and Rollnick compare this ‘guiding’ style of communication to being a good tour guide – tourists neither want to be marched around a city being told exactly what to eat and where to go, nor do they want their tour guide to follow them around aimlessly. ‘Guiding’ involves actively listening and providing expertise when asked for. In the case of the healthcare professional and patient, this means exploring what a disease diagnosis means for that person and how they can realistically make the changes required, while incorporating the practitioner’s expertise and knowledge of the disease where needed.

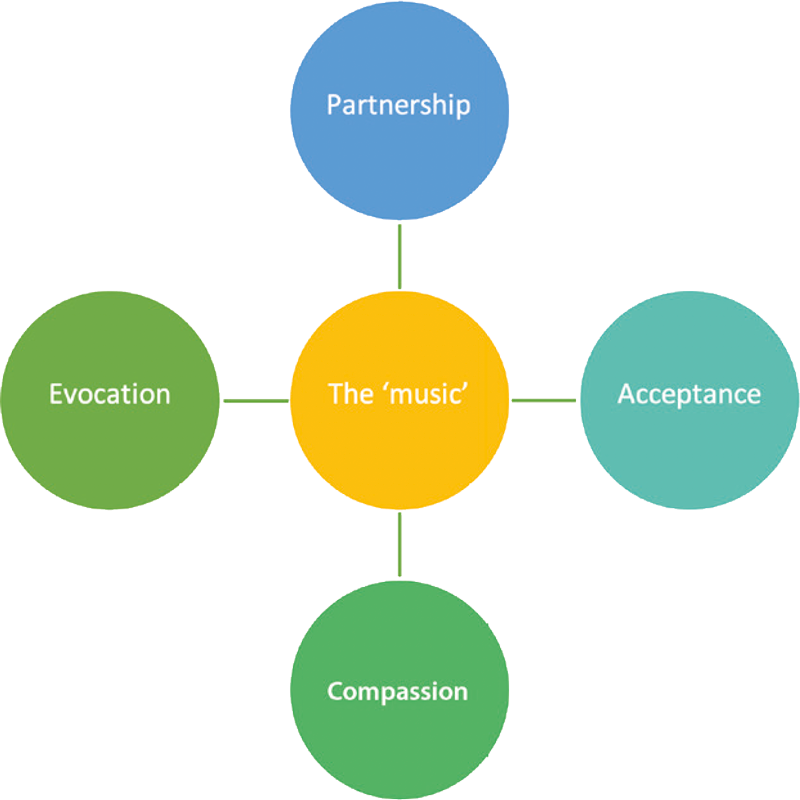

Figure 1. The spirit of MI.

Resisting the ‘righting reflex’

For those in a helping profession, it is only natural to want to get people on the right road to managing their health and wellbeing, or in a veterinary context, their animal’s health or their farm practices. Seeing a person head down the wrong road stimulates a natural desire to get out in front of them, use knowledge and expertise and say “Stop! Go back, I know there’s a better way for you over here, this option is better". It is done with the best of intentions, to fix what you see is going wrong and is known as the ‘righting reflex’. The righting reflex involves the belief that you must convince or persuade the person to do the right thing (Miller and Rollnick, 2013, p.10).

In other words, you just need to find the right argument, give that critical piece of information, provoke the right emotions, and the person will make the change. This belief informed addiction treatment during the 20th century; confront the person, provide the solution, and when you meet resistance just turn up the volume. This approach is not just used in addiction work, but in many settings in which professionals seek to help, such as animal health, human health, social care and the criminal justice system. However, it is believed that only about one in 20 people find this approach helpful, with others finding the opposite effect happening – they conclude that they do not want to make a change. While the arguments for and against a particular change are more than likely already within an ambivalent person, hearing a professional argue strongly for only one side (the pros of making a change) often results in their arguing against the change, in order to regain autonomy. Think of the smoker who is confronted with all the many dangers of smoking and responds that their 'grandmother smoked every day and lived until she was 105'.

The spirit of MI

Miller and Rollnick (2013) describe the spirit of MI (Figure 1) as the music that goes with the words. Without the underlying spirit, MI becomes a sales trick to use on clients to manipulate them – the expert trying to outsmart their adversary. There are four components to the spirit of MI. MI is a partnership and is used ‘for’ and ‘with’ a person rather than ‘to’ or ‘on’ a person, with the professional aiming to do less than half of the talking and eliciting client change talk. It promotes acceptance of what a client brings, supporting autonomy and expressing empathy. Compassion is a key element of an MI-consistent consult. It is based on the best interests of the clients and their animals and acknowledges that being ambivalent or ‘on the fence’ is a completely natural step towards change. Finally, much of the role of the professional is to evoke and strengthen their client’s own motivation for change, rather than pressing motivation upon them.

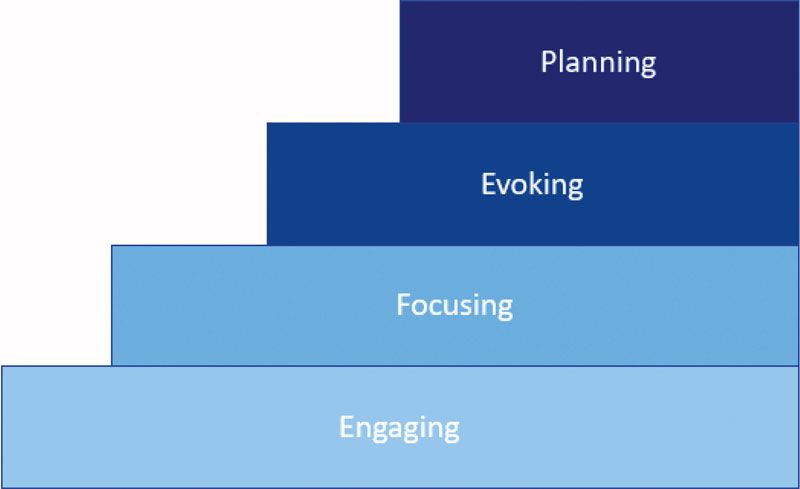

The four processes of MI

There are four central processes to form the flow of an MI consult (Figure 2). These do not necessarily happen in order and the duration of each stage is dependent on the consult, the topic and the client-practitioner relationship, so they are represented as stairs. Engaging is the establishment of a working relationship and provides the opportunity for the practitioner to gain a full picture. It is this initial engagement that tells a person how much they trust the practitioner, and whether they will return in search of help. It is a prerequisite for everything

Figure 2. The four processes of MI.

During the consult or working relationship, a direction towards one or more goals will emerge. This could be a specific treatment plan, a specific behavioural change, or a choice to accept something. Focusing helps to clarify direction and the changes that it is hoped will come out of the consult. Then comes the heart of MI – evoking or eliciting a person’s own motivation for change. It happens when you focus on a particular change and then harness the client’s own ideas and feelings about why and how they might do it. The opposite of this is the expert-driven approach where the practitioner finds what is going wrong and provides instructions to fix it. Here is an example: during an acute case of mastitis, a veterinary practitioner will prescribe an antibiotic, describing specifically the animal, dose, duration, and method of administration. However, when the goal being discussed is to reduce the incidence of mastitis on farm, changes to the farm routine may be required. This is where an expert-driven approach may break down. This kind of change requires the client’s active participation in the planning process, and an avoidance of the ‘righting reflex’ for the practitioner to support sustainable, meaningful changes.

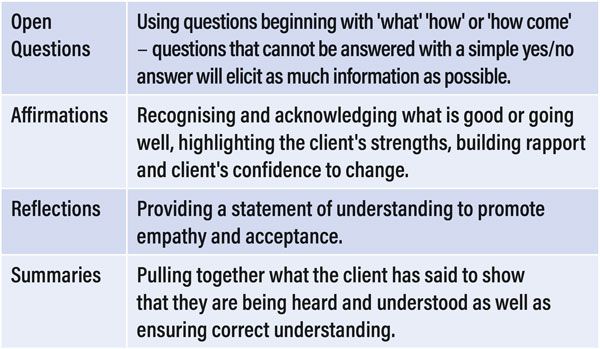

The core skills of MI

There are core technical skills for practitioners to learn to have effective, MI-consistent conversations, such as using OARS (Figure 3). Using these communication techniques can be subtle and should be embedded into how a practitioner communicates rather than them completely changing their consult style overnight. However, making these subtle changes can, over time, have a positive impact on the client-practitioner relationship, the achievement of shared goals or improving new graduates’ confidence when meeting new clients.

Figure 3. The core skills of MI: OARS. Source: Regan and Burrell, 2021.

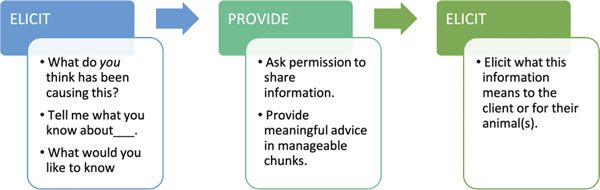

Using these strategies for exploring a client’s intrinsic motivation and resisting the ‘righting reflex’ does not mean that practitioners completely withhold their expertise and advice — consider once more the continuum of communication styles. Naturally, practitioners have knowledge that clients need and expect during a consult. However, within MI there is one key difference: rather than dispensing unsolicited expert opinion or advice using a directive style, this information and advice should be provided when it is asked for. There is a way of providing advice, with permission, that follows the spirit of MI. That is: elicit, provide, elicit (Figure 4).

Efficacy of MI

The efficacy of MI has been demonstrated within the health and social care field as a method for promoting behaviour change in the areas of substance abuse and physical activity (Frost et al, 2018). However, a small number of studies have also examined the efficacy of MI training within the field of veterinary medicine. Svensson et al (2020a) delivered an MI training programme, over six months, to 38 Swedish cattle veterinarians, finding a significant increase in the use of open questions, affirmations and reflections, and a decrease in the use of persuasive language during role play conversations, post training.

Figure 4. Elicit-provide-elicit structure of knowledge sharing.

An additional study by Svensson et al (2020b) found that vets who received MI training and achieved ‘moderate’ MI proficiency were 1.6 times more likely during consults with farmers to elicit client change talk, compared to vets who had not received training. Similarly, Bard et al (2022) delivered a short MI training programme of four to five hours to UK vets, finding a significant increase in MI-consistent behaviours and a decrease in MI-inconsistent behaviours during consults with farmers after training. Furthermore, a significant increase in farmer ‘commitment’ change talk was also found (Bard et al, 2022). ‘Commitment’ change talk implies intention to engage in a behaviour and is a predictor of behaviour change (Amrhein et al, 2003; Magill et al, 2014).

Currently, the efficacy of MI training for Irish vets is being investigated in the Teagasc-AHI funded AMU-FARM project. An initial cohort of vets have been trained in MI and data has been collected pertaining to skill development, self-confidence, satisfaction, and perceived usefulness of MI to veterinary practice, using questionnaire, written assessment, and interview/focus group-based methods.

Training in MI

Training in motivational interviewing is now available through Animal Health Ireland. An introductory eLearning module followed by in-person skill development workshops are available to those working in animal health. To sign up, please complete the expression of interest form in the training section of the AHI website: https://portal.animalhealthireland.ie/traineoi/

Conclusion

- The spirit of MI calls for partnership, acceptance, compassion and evocation.

- Rolling with ambivalence and fighting the ‘righting reflex’ are key to having collaborative decision-making consultations and achieving shared goals.

- There are four key processes in MI: engaging, focusing, evoking and planning.

- Using open questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries can elicit client change talk, increase their confidence to change, help gain a deeper understanding of the client’s situation and build rapport.

- Amrhein, P. C., Miller, W. R., Yahne, C. E., Palmer, M. & Fulcher, L. (2003) 'Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes', Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, pp. 862-878.

- Bard, A. M., Main, D. C. J., Haase, A. M., Whay, H. R. & Reyher, K. K. (2022) 'Veterinary communication can influence farmer change talk and can be modified following brief motivational interviewing training', PLoS ONE, 17, pp. 1-22.

- Frost, H., Campbell, P., Maxwell, M., O'Carroll, R. E., Dombrowski, S. U., Williams, B., Cheyne, H., Coles, E. & Pollock, A. (2018) 'Effectiveness of motivational interviewing on adult behaviour change in health and social care settings: A systematic review of reviews', PLoS One, 13, pp. 1-21.

- Gribben, L. & Burrell, A. (2023) 'The MAP model: Approaching behaviour change conversations on farm',

- Magill, M., Gaume, J., Apodaca, T. R., Walthers, J., Mastroleo, N. R., Borsari, B. & Longabaugh, R. (2014) 'The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of MI's key causal model', Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, pp. 973-83.

- Miller, W. R. & Rollnick, S. (2013) Motivational interviewing: Helping people change, 3rd edition, New York: Guilford Press.

- Regan, A. & Burrell, A. (2021) 'Communication innovation supports vet’s role in driving change in animal health management', Veterinary Ireland Journal, 11, pp. 407-409.81-83.

1. Motivational interviewing aligns most closely with which style of communication?

A. Directing

B. Guiding

C. Following

2. Evocation is when:

A. The veterinarian works ‘for’ and ‘with’ the client

towards change

B. The best interests of the client are prioritised

C. The client’s own motivation for change is explored

and strengthened

3. Convincing or persuading a client of the value of making a change (i.e., using the righting reflex) is most likely to result in the client arguing against the change

A. True

B. False

4. Which of the following is an open question?

A. Do you milk record?

B. Are you happy with the way you manage drying

off?

C. How important is it for you to reduce mastitis?

5. You must work through the four MI processes (engaging, focusing, evoking and planning) in order

A. True

B. False

ANSWERS: 1B; 2C; 3A; 4C; 5B.