Better communication between vet and herd owner: a US perspective

Based in West Lafayette, in Indiana, W. Mark Hilton, DVM, PAS, DABVP (beef cattle), senior technical consultant, Elanco Animal Health, provides a US perspective on entrepreneurial approaches to a deeper understanding of the needs of the herd owner

Progressive, entrepreneurial beef and dairy producers demand a level of service well beyond that which is traditionally described on a list of clinical skills common to practicing veterinarians. It is also known that progressive, entrepreneurial, bovine herd health veterinarians desire to offer services to their clients that are more consultative in nature so that they can become an asset to the herd owner. To become a trusted partner to the beef and dairy producer, the veterinarian must know the goals of the owner and how to communicate recommendations for reaching those goals.

Introduction

Traditional tasks of pregnancy-checking cows, performing breeding soundness examinations on bulls, processing calves, Brucellosis vaccinating, DA surgeries, dystocias, and diagnosing and treating sick cattle have been the backbone of bovine veterinary practice for many years. If bovine veterinarians want to remain viable into the future, they must provide these services and add additional services that are beyond what we have relied upon for many years.

This is no different from the shift in the mindset of the most progressive clients. Are these producers still in charge of every task on the farm or ranch, or have they trained others in the operation to do some of this labour so that they can spend more time working on the business to be more profitable? To perform more value-added services for producers, veterinarians must be more aware of their client’s goals and priorities, and the veterinarian must ask the client for this information.

After discussion of the client’s goals and priorities, it is paramount that the herd health veterinarian develop a programme for success that is tailored specifically to that cattle business. Our goal as the herd health veterinarian is to become indispensable to the client so that whenever they think ‘cattle’, they think of us first. We may not know the answer to their question, but we want to be the first person that comes to mind because we have developed a trusted relationship where they know that if we do not know the answer, we will find it. In this relationship, we become the ‘coach’ of the beef or dairy team and we assemble the trusted advisors that will strengthen our relationship with all team members.

Growing your practice

If your goal is to grow your veterinary practice, what are ways you can do that? Some thoughts are that you could expand your practice radius, but the downside of this idea is more time driving and in most cases the mileage fee is not a significant profit centre. If herds on the periphery of your practice radius are large enough that you spend the majority of the day at these farms, then this can be a viable strategy. You could add a haul-in facility and that would allow you to eliminate drive time, which would allow you to see more cases in a day.

Many beef veterinarians have done this and find it especially beneficial for doing breeding soundness exams (BSEs) and seeing individual sick animal cases that can be safely brought into the clinic. Some clinics have trained or added a Registered Veterinary Technician that can perform tasks that are legal for them according to your state practice act. Another option is to offer additional services to the clients that are already in your client base. The caveat to this approach is that you have to offer something that adds value to the producer’s beef or dairy business. In addition, you must know that the client really needs this service.

The key to adding an additional service to your existing clients is to always ask them their goals. Do we regularly do this? One study concluded that: “Veterinarians that do not clearly seek the views of their clients, often do not fully engage in the advisory process.” Their study showed that only 24 per cent of the time did the veterinarian and producer set herd performance goals. Veterinarians who did not set goals indicated that they and the producer “intuitively knew” what each wanted to achieve, and that the setting of these performance goals was considered “too formal”. Veterinarians often could not identify a producer’s main goal.

During on-farm conversations, veterinarians did not actively seek to identify the producers’ goals or problems, suggest a co-operative strategy or summarise any advice given. These results should be an embarrassment to any veterinarian that does bovine work. The study also concluded that the veterinarian needs to actively seek out the goals of the producer because the producers did not readily volunteer this information. The awareness of the producer’s goals is paramount to compliance by the producer and successful attainment of the producer’s goals. If we want to become an asset to the producer, we must stop telling them what to do and instead seek to understand their top priorities for the improvement of their business. Focus on perceived benefits and remove or reduce barriers to successful implementation of a solution. Producers perceive the veterinarian as an appreciated, important, and frequently contacted information source. In one study, producers stated that they appreciated their veterinarian organising “producer study groups” to collaborate on specific health issues.

Our practice developed a total beef herd health programme and we invited the clients that were a part of that programme to a ‘year-end’ meeting each January. The meeting consisted of a talk on a subject of importance to the group and concluded with a ‘round-table’ discussion where the producers shared their successes and failures of the previous year. Many of the clients stated that it was the best meeting they attended all year. Producers learning from each other and being leaders in specific areas turned out to be one of our best ideas ever for sustaining and growing our beef cow-calf production medicine programme.

Communication/creating demand for advice

The prevention of complex problems requires customised communication strategies as well as an integrated approach. Two factors of producer mindset are the most important behavioural determinants for improvement: believing there is a problem in the herd and belief in the effectiveness of management to solve that problem. These two keys become the template on how to initiate a production medicine programme. The programme needs to be customised to the specific livestock business and the owner must believe that some aspect of their business can be improved with input from the herd health veterinarian. It is imperative that the producer takes ownership in the thought that improvements can be made. To close the loop in production medicine consultation, the solution must be reasonable to accomplish and the owner must validate the solution.

The more the owner takes possession of the concern and the solution the more likely the change will happen. If the veterinarian identifies the concern and the producer feels that we are telling them what to do, the chance for success becomes minimal. Ask the producer their goals (ensure they share ownership of the concern), propose a solution and ask if the solution is reasonable. If a solution is unknown at the time, this is not a concern. Many problems will be complex in nature and will take time for the veterinarian to develop a plan to solve the problem. The key is to respond to the client in a reasonable timeframe to propose the solution. In my experience, the veterinarian is thought of just as highly if they immediately know the solution or if it comes after some research.

Use open-ended questions, such as, “What are your short-term and long-term goals for your agricultural business?” If there are multiple decision-makers in the business, these goals need to be universally accepted. Be sure to ask the entire management team so that you can get buy-in from everyone on the team. After the producer states the goals, the herd health veterinarian should ask, “How can our veterinary business help you achieve these goals?” It has been my experience that when you ask about goals and how your business can be an asset to your client’s business, you develop a stronger business relationship. Other businesses that deal with this producer are not asking these questions. The fact that we are asking them puts us in a stronger position to become an asset to the producer’s business.

It may seem obvious, but we have all seen countless examples of a producer not using a service of a veterinary clinic because they were unaware of the service or the service did not exist. The most important steps in creating demand for a veterinary service is to offer the service and let the producers know that the service is available. Newsletters, client education meetings, and speaking at local sponsored events are great ways to introduce a new service or market an existing, but under-utilised service. If your clinic has a website, this can be a great way to announce new services. Adding timely client educational pieces to your website is another technique you can use to show that you are the veterinary clinic that has client education at the centre of your business model. The goal is to raise producer awareness about the importance of a particular subject in order to stimulate demand for services that address the issue.

An improvement in communications skills will be necessary to become more of an advisor to beef and dairy producers. According to dairy producers, veterinarians have difficulties in being proactive advisors and applying essential communication. Research has found that producers say that veterinarians are persistent in their curatively-oriented, prescriptive, reactive expert role that prevails in veterinarian-farmer contacts. These producers’ advice is that veterinarians should take on the role of coach, ‘sparring partner’ and facilitator instead of being merely a technical expert.

Just as veterinarians have different ways of learning and using information, so do producers. Communication strategies need to be customised to the specific learning style of each client. Producers may be segmented into information seekers, do-it-yourselfers, wait-and-seers, and reclusive traditionalists, according to research. While one beef producer may be quickly convinced to make a herd management change if informed “you will save $5,000/year by limit feeding your hay vs. supplying it ad lib”, another producer might decline because he does not see how the change is possible. While not every producer will heed the advice given, others that initially decline will make changes if you ask additional questions. Asking probing questions will provide a deeper understanding of an issue or topic.

Another key to the communication strategy is to utilise a team of experts, e.g., nutritionist, forage specialist, banker. These outside experts can bring a level of expertise that the veterinarian does not possess and the veterinarian can then more thoroughly concentrate on areas of their expertise. Another advantage of having additional advisors is that the outside expert may repeat something that was mentioned by the herd health veterinarian in an earlier visit. This suggestion may be made in a similar or different way, but now it is seen or heard in a different light. Even though the advice may be ‘old’ to the client, the advice may be heard through ‘new ears’ and may now be taken. The goal is to help the producer achieve success and who gets the ‘credit’ for helping should not matter.

As a consultant, we must not be impatient when it comes to herd improvements. Even when a client identifies a need and we provide a solution, it may take years to implement the change. Herd concerns are generally long-term problems that may have taken years to develop. A problem that took years to develop will likely take months or years to be fully resolved.

Veterinary Business Plan

When your veterinary business commits to adding or expanding its consulting role, everyone on the veterinary team must be in alignment on this plan. While the entire team must embrace this philosophy, individuals on the team can and should have various levels of expertise. One of the benefits to having a team in a veterinary business is that some members may be experts in fertility while others have more proficiency in nutrition or genetics.

If you, the veterinarian, are going to be giving financial advice, and bovine consulting nearly always has a financial component, it makes sense that you need to have a veterinary business plan of your own. When I was in practice, my partner and I sat down every January and pored over our previous year’s financial statements. We made a business plan for the upcoming year and took a more long-term view of where we thought the business was heading. This proved to be extremely valuable time spent for the health of our business.

Traits of the proper veterinary advisor

or coach

A survey of Dutch dairy producers asked them to identify traits that would describe a proper veterinary advisor or coach. Their list included:

Understands entrepreneurship

Has empathy for producer; is not dominant

Is technically well-skilled

Strong in communication

Invests in many contact moments

Has a practice business strategy

Knows behavioural economics principles

Is analytically skilled

Strong in choices of products and services

Has a commercial attitude

Shows great creativity

Separates advisory work from technical work at visits

Attends continuing professional training

Defines tailor-made products for the farm

As you analyse the list above, only four of the fourteen items are related to technical ability (3, 9, 13, 14) while ten of the fourteen are more related to communications, business and consultation. Entrepreneurial producers want and expect a veterinarian that can help them reach their goals. Look at each trait on the list above and ask yourself, “Does this statement describe me and my practice?”

In the same survey, producers were asked, “What would you consider as weaknesses of your veterinarians?” Answers included:

- Too dominant attitude in profession

- Talks too much; listens too little

- Rather poor communication skills

- Does not follow structured protocols

- Does not provide clear work instructions

- Limited knowledge of cow nutrition

- Limited knowledge of management

- Limited knowledge of farm economics

- Poor knowledge of entrepreneurship

- Knows little about farm organisation

- Tells little about fields of expertise

- Does not show what he contributes to farm

- Is not proactive; waits too long before taking action

- Does not offer on-site training

- Too many changes in personnel in practice

- Maybe not willing to invest in discussion

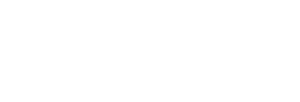

Table 1. Score means and statistical comparison of scores recorded for herd veterinarian vs ideal veterinarian. Source: Cipolla, M., & Zecconi, A. (2015). Study on veterinarian communication skills preferred and perceived by dairy farmers. Research in veterinary science, 99, 60-62.

Look at this list and critically analyse yourself. Which of the above would clients say about you? Also, note that not one of the above list says anything to do with the veterinarian’s clinical skills. We are strong in these areas and our clients see this. Look at the list again and see where you need to improve.

A study of dairy farmers in Italy showed that producers’ scores for their “ideal veterinarian” significantly differed from their herd veterinarian in several categories where a score of one was the lowest grade and five the highest one (Table 1).

In human medical studies, patient trust and good interpersonal relationships with the primary care physician are major predictors of patient satisfaction and loyalty to the physician. Patients need to trust the primary care physician to be satisfied and loyal. I am confident that this would also apply to veterinarians.

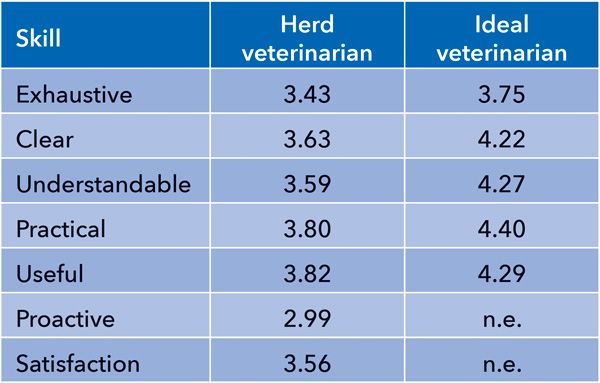

Figure 1. Three-stage collaboration model. Source: Atkinson, O. (2010). Communication in farm animal practice 1. Farmer‐vet relationships. In Practice, 32(3), 114-117.

Relationship models

Different clients will demand different kinds of collaboration, depending on their own experience, knowledge and inclination to collaborate. This has been modelled into three different stages (Figure 1). In the ‘You phase’, the farmer is primarily dependent on the veterinarian and may trust the veterinarian to make decisions and define the objectives and action to be taken. The ‘I phase’ is characterised by a farmer acting largely independently, with the veterinarian being regarded as a provider of a certain means to an end. In the ‘I phase’ the farmer is in full control of the relationship and may use the veterinarian just as a technician, or possibly only as a writer of prescriptions and/or dispenser of medicines. Finally, the ‘We phase’ sees both the farmer and veterinarian collaborating to achieve common goals previously defined together.

Entrepreneurial producers are willing to pay for advice, provided it is clear in advance what the benefit or profit will be. The consultation visit must be separate from the clinical visit. The client needs to clearly understand that they are paying for advice, not labour. Turn off your phone and give the client your full attention.

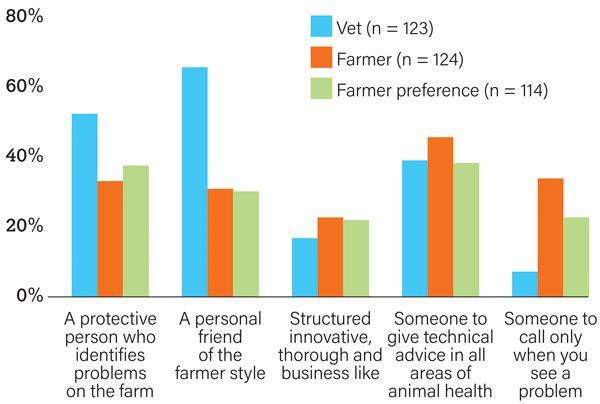

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of veterinarian and farmer responses to the question: “How do you present yourself to your dairy clients?/What approach to you and your farm do you feel your veterinarian has?/What approach would you prefer your veterinarian to have?” Source: Hall, J., & Wapenaar, W. (2012). Opinions and practices of veterinarians and dairy farmers towards herd health management in the UK. Veterinary Record, 170(17).

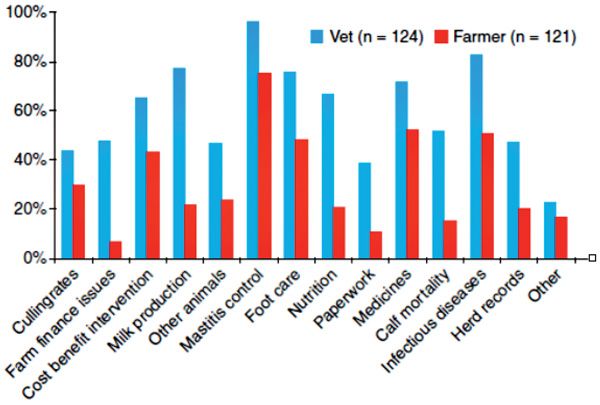

The majority of farm respondents (98 of 121; 81 per cent) valued their discussions with their herd health veterinarian, and it was apparent from the relatively small proportion of veterinarians initiating a discussion on farm (33 of 125; 26 per cent) that there is the opportunity for a more proactive approach from veterinarians. Dairy veterinarians and producers in the UK were asked about recurrence of topics of discussion and in all 14 categories veterinarians thought the topic of discussion occurred more frequently than did the producers. (Figure 3). The point of this discrepancy is not to determine who is correct, but how to improve communication and listening skills. If two parties are having a discussion and they are interviewed later, the response to “Was this discussed?” should be equal for both parties. In the same study, consultation time was perceived as valuable by 78 per cent of veterinarians and 81 per cent of farmers who both agreed that ‘discussions were good advice to put into practice’.

Figure 3. Frequency distribution of veterinarian and farmer responses to the question: “During these visits to your dairy clients which topics of discussion recur?/During visits by the veterinarian, which topics of discussion recur?” Source: Hall, J., & Wapenaar, W. (2012). Opinions and practices of veterinarians and dairy farmers towards herd health management in the UK. Veterinary Record, 170(17).

Practice culture and philosophy

If the veterinary business has not embraced, or minimally embraced, the consultative role, the shift in practice philosophy can still occur. To shift the culture of the practice, it will take buy-in from all team members. This also requires a programme leader within the clinic who will lead this transformation. While all team members need not participate in the production medicine or herd health programme, all members must see this ‘thinking’ work as valuable to both the producer and the veterinary business. Time for research and writing herd reports must be placed on the clinic schedule and interruptions of this scheduled time must be kept to a bare minimum. In time, the veterinary team will realise that consultation time is just as important as clinical time.

How does a veterinary business change from a clinic that does not offer, or minimally offers, these production medicine programmes? The answer is simple; the most important way to create demand for a new veterinary service is to offer the new service. Ask your clients what they want, ask them their goals and ask how you can help them achieve them. Ask, ask, ask. Do not tell them what to do. Do not think for them. See action plan for consultation, Figure 4.

References available on reques

Action plan for effective consultation

- Veterinarian establishes trust with producer

- Veterinarian asks producer their goals

- Producer defines and refines the goals

- Veterinarian asks producer for possible solutions

- Veterinarian and producer discuss proposed solutions

- Veterinarian and producer explore any unintended consequences

- Veterinarian and producer agree on action plan

- Veterinarian and producer agree on how to measure progress

- Veterinarian and producer analyse results:

- Results are positive → move to next goal

- Results are negative → re-examine goal and possible solutions

Figure 4.

One of the most important things a veterinarian can do to become an asset to the herd owner and take on more of a consultative role is to:

A. Ask the owner if the prices charged for veterinary services are reasonable

B. Pass on any rebates on medications to the farmer

C. Ask the owner his or her herd goals

D. Tell the owner about successes you are having at other farms

2. As a veterinary consultant, it is important to:

A. Develop a team of experts to call on when the herd owner has questions

B. Know enough about each area of the cattle operation to provide all answers

c. Have someone in your office that is an expert on each area of cattle production

d. Find what works on one farm and apply that information to your other farms

3. Who needs to be the initiator of a discussion

on herd goals?

A. Owner

B. Manager

C. Worker

D. Veterinarian

4. A very important key to having successful implementation of a new idea is for:

A. The owner to take possession of the concern and solution

b. The veterinarian to take possession of the concern and solution

c. The veterinarian to give examples of all that will go wrong if the plan is not followed

c. The veterinarian to tell the owner that all his/her other clients are doing this

The most important steps in creating demand for a veterinary service are to:

A. Keep the price at a low enough level and promote that price

b. Offer the service and let the producers know that the service is available

c. Ask your clients to tell others about the service and reward those that refer to you

d. Discount the price for the first few months and then slowly raise the price

ANSWERS: 1C; 2A; 3D; 4A; 5B.