Focus - Companion animal - September 2019

Canine ophthalmic emergencies – part 2

The first article on canine ophthalmic emergencies, which featured in the August issue of the Veterinary Ireland Journal, reviewed globe proptosis, glaucoma, anterior lens luxation and sudden onset blindness. This follow-up article reviews ocular trauma leading to eyelid lacerations, corneal lacerations and corneal foreign bodies, along with melting corneal ulcers and descemetocoeles. These conditions are common presentations to general practice, and require prompt treatment for the best possible outcome, writes Natasha Mitchell MVB DVOphthal MRCVS

Eyelid lacerations

Traumatic laceration to the eyelids usually results from fights or cat scratches. Prevention of self-trauma and protection of the cornea with topical lubrication are important. An ocular examination will determine if any other structures are involved, such as the cornea, sclera or nasolacrimal apparatus, and hyphaema or uveitis could be present. The eyelids are very well vascularised and, thus, usually heal well in the absence of infection. Most traumatic injuries involve the eyelid margin, and this needs to be repaired precisely in order to re-establish the smooth architecture without any notch defects that could result in trichiasis, conjunctivitis, keratitis or corneal ulceration.

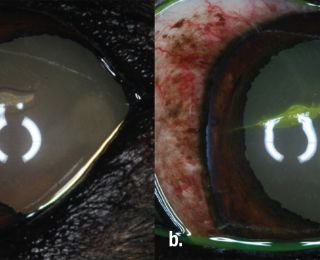

Rapid repair results in the best outcome, but the patient needs to be stable and suitable for general anaesthesia. If surgery cannot be done promptly (within 24 hours), the wound is treated with antimicrobials and anti-inflammatories until such time as anaesthesia and surgery are possible (Figure 1).

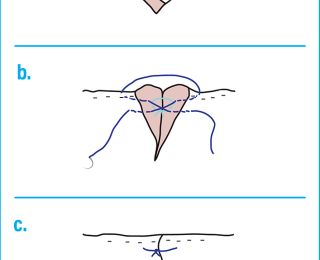

During surgery, resection of eyelid tissue is avoided if possible. The sutures, and particularly the knots, need to be kept away from the cornea, and this is achieved using a two-layer closure with a figure-of-eight suture at the eyelid margin (Figure 2).

Absorbable 6/0 suture material on a reverse-cutting or spatulate needle is appropriate. Standard post-operative treatment includes an Elizabethan collar, topical antibiotic ointment, systemic antibiotics and NSAIDs, and good wound hygiene.

Corneal lacerations

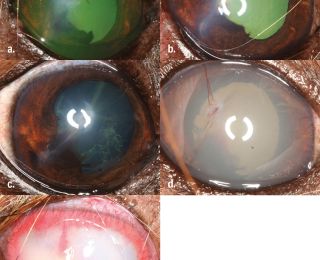

Corneal lacerations usually result from cat claw injuries. Careful examination is required to assess the limits of the laceration (checking if it extends over the limbus), the depth of penetration and the presence of any eyelid or lens injury. Fluorescein should be applied to assess corneal integrity by way of the Seidel test.

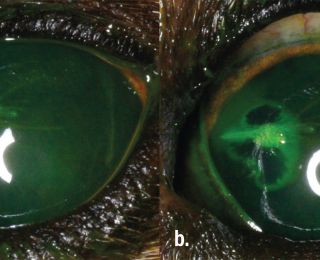

A drop of sterile fluorescein is applied to the eye. If a perforating (full thickness) corneal wound is present, it may leak aqueous humour. This is visualised as black rivulets of aqueous emerge from the wound, diluting the bright green fluorescein dye (Figure 3).

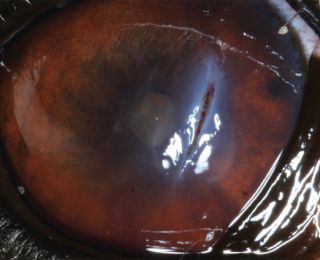

Perforating injuries may be associated with hyphaema, iris prolapse, fibrinous uveitis, hypopyon, anterior chamber collapse and lens rupture. Extension of the laceration beyond the limbus and into the sclera may be associated with damage to the underlying ciliary body, which can lead to retinal detachment. Rupture of the anterior lens capsule can result in severe and progressive phacoclastic uveitis that requires urgent and aggressive treatment in order to save the eye. Intraocular bacterial infection can also result in delayed septic implantation endophthalmitis. If the lens has been damaged, or if the laceration extends over the limbus, prompt referral should be recommended, as surgical lendectomy may be required.

Superficial corneal lacerations (Figure 4) are treated similarly to an uncomplicated ulcer, and tend to heal well. If there is a loose flap of epithelium and anterior stroma, this can be sharply resected to aid healing. Deeper lacerations (Figure 5) that result in gaping of the wound edges resulting in poor corneal apposition require corneal suturing with 8/0 or 9/0 absorbable suture.

Corneal oedema can seal a full-thickness defect temporarily, but repeated leakage can still occur, so repeated review is necessary, and referral is recommended if there is any doubt. Loss of aqueous (often observed as a gelatinous aqueous clot Figure 6), from the anterior chamber or uveal prolapse (Figure 7) are further indications for corneal suturing.

This is a microsurgical procedure that requires use of appropriate magnification, small suture size (8-0 to 10-0) and expertise, so referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist is recommended. The length of a lens capsule tear is sometimes used as a prognostic factor to determine whether medical or surgical treatment is appropriate. However, this can be difficult to determine if there is hyphaema or fibrinous uveitis. Early prophylactic lens removal to prevent vision-threatening complications such as glaucoma and endophthalmitis is recommended when there is substantial disruption of the lens cortex, or for lens capsule tears of 1.5mm or greater (Figure 8). Fibrinous uveitis associated with lens capsule disruption can lead to subsequent fibrous metaplasia of the anterior lens capsule with sufficient repair to avoid the need for surgery in cases with small tears. Medical management with topical antibiotics and mydriatics in addition to systemic broad-spectrum antibiotics and NSAIDs are required in all cases.

Corneal foreign body

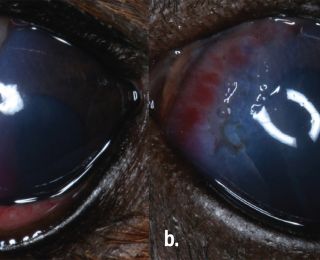

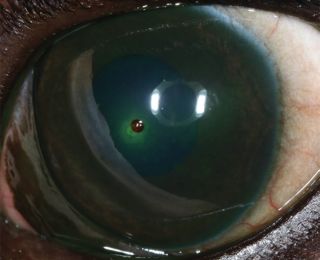

Superficial foreign bodies (eg. flakes of paint, husks of plant seeds, Figures 9 and 10) initially adhere to the tear film with surface tension, but with time they can become embedded within the corneal epithelium and superficial stroma (Figure 11 and 12).

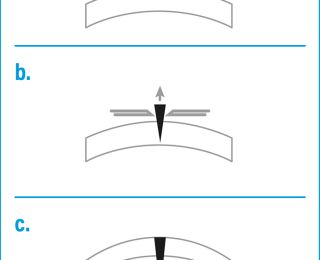

They may be difficult to see if they induce chemosis, or are located either behind the nictitans or deep within the conjunctival fornices. Superficial corneal foreign bodies can often be removed under topical anaesthesia alone by hydropulsion (flushing) or by gentle debridement with a cotton-tipped swab a 23-25G needle. Foreign bodies that are more deeply embedded within the cornea require more cautious removal under general anaesthesia, as they may be penetrating (with an entry wound) or perforating (with both an entry and exit wound, ie. full thickness). A seidel test is used to assess for aqueous leakage and the pupil should be dilated to determine if there is damage to the anterior lens capsule. A foreign body may injure the cornea but not be present at the time of examination, and usually a tract is visible along the course of entry/exit, with resulting inflammation. The techniques appropriate for removal depend on several factors, and are illustrated in Figure 13. Splinters and thorns may be removed by incising any overlying cornea using a microsurgical scalpel blade, and then carefully dislodging them with a fine needle. Corneal suturing or graft placement may be required depending on the size and depth of any resultant stromal defect. Penetrating foreign bodies may be approached externally by impaling them with two needles and removing them, followed by suturing of the corneal wound.

However, in the case of a barbed thorn or when the majority of the foreign body is already within the anterior chamber, removal via a remote corneal incision may be necessary. After inserting viscoelastic through a 3mm corneo-limbal incision, a forceps is inserted into the anterior chamber to gently pull the foreign body deeper into the eye, until it is free and can be removed through the surgical incision. Both the wound created by the foreign body and surgical incision in the peripheral cornea will require surgical repair. Postoperative management with topical antibiotics and mydriatics, and systemic NSAIDs is appropriate. Penetrating corneal injuries should also be treated with systemic antibiotics.

Melting corneal ulcers

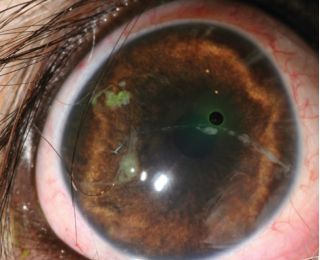

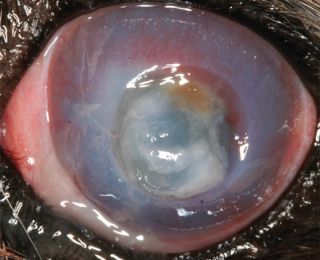

Liquefactive corneal necrosis, or corneal ‘melting’ is a very serious potential complication of all forms of corneal ulceration. It occurs following liberation of proteolytic collagenase enzymes from invading microorganisms, white blood cells or keratocytes, which cause rapid collagenolysis and loss of corneal structure. The cornea appears white and soft, with an altered globe contour (Figure 14). Progression to corneal perforation is rapid, therefore prompt and intensive treatment is required (Figure 15).

Treatment should include:

- Topical antibiotics frequently (every one to two hours), preferably based on examination of cytological specimens from the ulcer margins. After 24 hours, the eye is reviewed, and less frequent drops may be appropriate by then;

- Systemic antibiotics. Doxycycline may be a good choice as it also inhibits matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that can cause melting. However, it has no effect against Pseudomonas spp., so an alternative antibiotic, such as a fluoroquinolone, may be a better choice in that case;

- Anticollagenase medication is essential in the case of melting ulcers, and either heterologous or autologous serum is most commonly used and the most effective; initially everyone to two hours until stabilisation is achieved. Alternatively, acetylcysteine (Ilube, Rayner Pharmaceuticals Ltd, UK) may be used;

- Secondary uveitis is always present, so topical treatment with atropine 1% is used (unless contraindications of keratoconjunctivitis sicca [KCS] or glaucoma), usually once daily for about three days;

- Systemic NSAIDs are useful to reduce ocular pain and help to stabilise the blood-ocular barrier. They reduce migration of leukocytes to the ulcer, which may be the source of the destructive collagenase enzymes;

The use of an Elizabethan collar is recommended to prevent self-trauma.

Frequent re-examination will be essential during the early stages of medical treatment to ensure the ulcer does not become deeper, get infected, or that the globe does not rupture. Surgery may also be required for melting ulcers, to remove necrotic corneal tissue and stabilize the cornea, and therefore referral should be considered early. There are various surgical procedures that may be appropriate to an individual case. The advantages include tectonic support, blood supply delivering serum and systemic medication to the site and fibroblast supply for repair.

A 360-degree conjunctival flap does not necessitate any corneal sutures, and so may be useful as a salvage technique if the melting is extensive. Otherwise a conjunctival rotational pedicle or bridge flap may be appropriate.

Descemetocoele/iris prolapse

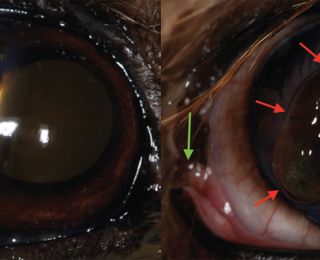

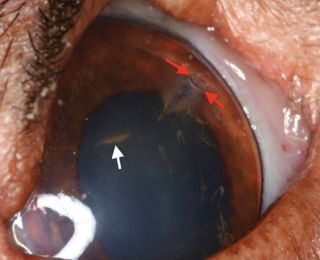

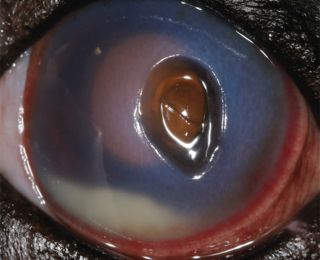

A deep stromal corneal ulcer becomes a descemetocoele when the overlying stroma and epithelium are completely lost, exposing Descemet’s membrane. The base of the ulcer is typically clear, with the iris or tapetal reflection visible through it (Figure 16).

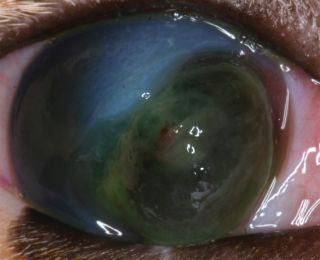

The base does not stain with fluorescein, as there is no stroma present to uptake it. The exposed side walls of the ulcer will uptake fluorescein however. A descemetocoele is an emergency because Descemet’s membrane can easily rupture as it is an area of structural weakness. In that case, aqueous humour leaks and rapidly clots as fibrin develops, and the iris moves forwards to plug the leak because of the rapid drop in intraocular pressure (IOP). The iris may be visible if it prolapses through the perforation (Figures 17 and 18).

Siedel’s test is useful to assess the integrity of the cornea. Initial medical treatment for a descemetocoele is similar to the treatment given for melting corneal ulcers. Unless infection or active melting are present, topical treatment does not need to be given as frequently – usually six times daily. Surgical repair is the recommended standard of care, whether the cornea has perforated or not. A conjunctival rotational pedicle or bridge flap may be sufficient in the case of a small descemetocoele, but conjunctiva is thin and may not provide sufficient structural support. A sliding corneo-conjunctival transposition transposes clear cornea into the area of the defect, allowing for transparency in this region (which is often central or within the visual axis) after healing. The transposed tissue is also stronger than conjunctiva alone and thus provides more mechanical support than a thinner conjunctival flap, and it is suitable to use for a focal full-thickness deficit.

Additionally, if the iris is prolapsed through a corneal perforation, it needs to be amputated if devitalised, or flushed and replaced if viable. Technical expertise, microsurgical instrumentation and magnification with an operating microscope, are required for these procedures. Enucleation could be considered if there is a negative dazzle reflex or a negative consensual pupillary light reflex, as these signs would indicate a poor prognosis for regaining any vision. Enucleation may also be necessary with severely damaged eyes, and referral is worthwhile if there is doubt as to whether an eye can be saved. A third eyelid flap isn’t recommended for a descemetocoele as it can trap infection, put pressure on a fragile globe and reduce penetration of essential topical medications. Any form of stromal puncture such as a grid or punctate keratotomy is contraindicated, as it is in any stromal ulcer.

Summary

The clinician may be presented with a wide range of ocular emergencies that require a rapid diagnosis and accurate intervention for the maintenance of vision and the globe. A good knowledge of the basic principles of ophthalmology, combined with careful assessment, using analgesia and anaesthesia as required, allows the clinician to make the most appropriate decision for the patient - referral or prompt treatment. Depending on the severity, eyelid lacerations, superficial corneal lacerations, some melting ulcers, and non penetrating corneal foreign bodies can be treated in practice. However, descemetocoeles and deep corneal lacerations or perforations are best referred where possible, having given appropriate initial treatment.

- Slatter’s Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology. 2018. Sixth edition. Maggs, Miller & Ofri. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-44337-1

- BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Ophthalmology. 2014. Third Edition. Edited by David Gould and Gillian McLellan. ISBN 978-1-905319-42-8

- Handbook of Veterinary Ophthalmic Emergencies. 2002. First Edition. David Williams & Kathy Barrie. Edited by Thomas Evans. ISBN: 978-0-7506-3560-8

1. Poor surgical repair of the eyelid margin can lead to:

a - Trichiasis

b - Conjunctivitis

c - Corneal ulceration

d - All of the above

2 The most appropriate suture material for eyelid laceration repair is:

a - Absorbable 6/0 suture material on a reverse-cutting needle

b - Non-absorbable 6/0 suture material on a round-bodied needle

c - Absorbable 9/0 suture material on a spatulate needle

d - Absorbable 4/0 suture material on a conventional cutting needle

3. The most appropriate suture material for corneal laceration repair is:

a - Absorbable 8/0 suture material on a reverse-cutting needle

b - Non-absorbable 9/0 suture material on a round-bodied needle

c - Absorbable 9/0 suture material on a spatulate needle

d - Absorbable 8/0 suture material on a conventional cutting needle

4. Corneal collagenolysis “melting” is caused by:

a - Trauma

b - Corneal foreign body reaction

c - Severe secondary uveitis

d - Proteolytic enzymes acting on the collagen

5. The recommended standard of care for a descemetocoele is:

a - Hourly topical anticollagenases and antibiotics

b - Surgical repair with a corneo-conjunctival transposition

c - Third eyelid flap

d - Grid keratotomy

Answers: 1 d; 2 a; 3 C; 4 d; 5 b